The Land of the Lune

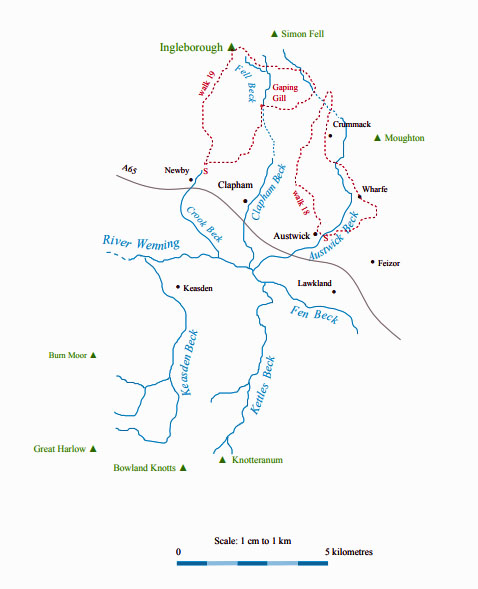

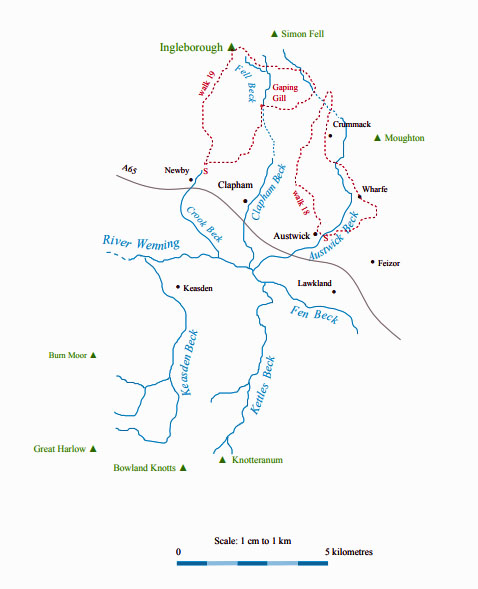

Chapter 10: The Wenning Headwaters

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Gretadale and a little more Lunesdale)

The Next Chapter (Wenningdale, Hindburndale and Roeburndale)

Austwick and Norber

The River Wenning ...

The Wenning has the most dramatic birth of all the

Lune’s tributaries. It springs forth at Swine Tail

just below Ingleborough’s plateau, gathers a few

more becks to form Fell Beck, and then plunges headlong

into the awesome chasm of Gaping Gill, Britain’s most

famous pothole.

Right: Gaping Gill

Right: Gaping Gill

The waters fall 111m, making it Britain’s largest

unbroken waterfall, according to the Guinness Book of

Records. The hole was first descended (intentionally) in

1895 by the French caver, Edouard Martel. He mapped

the main chamber, which is large enough, it is often said,

for York Minster to be fitted in. However, the latest laser

technology has measured the chamber as 136m by 46m,

and therefore the nave and transepts of the minster (at

159m by 75m) would be seriously damaged by any such

attempt.

You can judge for yourself by taking the winch that

local potholing clubs fit up at bank holiday weekends.

It is often said that it is free to go down ... but there’s a

charge to come up. In fact, they insist that you pay at the

top, in case you should disappear forever underground.

No, I must be fair: they are most solicitous about our

well-being and careful to count us all down and count us

all up again.

It is certainly an unforgettable

experience, as you sink slowly in

the cage below the diminishing

skylight, past the green, then grey,

then black, walls of the cavern, in

the shower of Fell Beck (although

most of it has been kindly diverted

away). On the floor of the cavern,

the water largely percolates

away through the boulders and

it is possible to scramble around

searching into various crannies of

the chamber. After a while, non-troglodytes would like to escape

– and then a problem becomes

clear: what goes down must come

up. On the surface, a numbered-ticket queueing system enables you

to lounge around, having a picnic,

smiling as people return drenched

and blinking, as you wait your

turn. Below, there isn’t: you must

stand in line. And if you waited 45 minutes in the sun on

top, you will have to wait 45 minutes in the cold, dark

Fell Beck shower below (or even longer, as potholers

tend to enter the cavern from elsewhere and lazily take

a ride out).

I see that there is now a leaflet advertising these

bank holiday treats and that the winch now operates for

a week. It’ll be a permanent tourist attraction soon, with

a snack bar and souvenir shop nearby, and umbrellas for

the queue below.

The geology of Gaping Gill is as we have come to

expect. Water streams off the gritstone on the eastern

slopes of Ingleborough and then disappears into the

limestone layer. Faulting has occurred at Gaping Gill to

enable such a large chasm to form. The Fell Beck water

then makes its way underground over the impermeable

slate and eventually emerges in Clapdale at the cave

spring of Beck Head to become Clapham Beck.

Left: Trow Gill

Left: Trow Gill

Potholers have found a difficult and dangerous way

through from Gaping Gill to Beck Head but over ground

we must make our way through the more appealing Trow

Gill. This is a dry gorge, with boulders heaped at the top,

between steep limestone cliffs. Trow Gill was caused by

a flood of meltwater after the Ice Age.

Below Trow Gill we enter Clapdale. On its eastern

side runs Long Lane, which is part of an ancient track

from Ribblesdale. From it, Thwaite Lane, an equally

ancient track that used to lead to Fountains Abbey,

heads east. As Long Lane approaches Clapham it passes

under two dank tunnels, built to protect the privacy of

Ingleborough Hall, a hall with no view of Ingleborough.

The Pennine Cycleway, which we met in the Lune

Gorge, passes through these tunnels, which must form

the only part of the cycleway upon which cyclists are

advised not to cycle!

On the west bank of Clapdale is Clapdale Drive,

which provides the most gentle of Dales walks. The

Farrer family created the drive for the carriages of guests

at their Ingleborough Hall in Clapham and, later, tourists

arriving by train at Clapham Station. Below a gate, the

drive becomes an artificially delightful environment

of trees, shrubs and lake, forming the Reginald Farrer

Nature Trail. As was the fashion, a grotto was added

to provide a romantic character that was presumably

perceived to be lacking. You may test your skill at

identifying trees and shrubs by ticking off ash, beech,

box, chestnut, European silver fir, larch, laurel, holly,

holm oak, Norway spruce, red oak, rhododendron, Sitka

spruce, Scots pine, and no doubt several others. Do not,

however, stray from the trail in your search, as there are

many warnings of “hidden dangers”, which I think mean

that you will be mistaken for a pheasant and shot.

By the cross in Clapham there is a footpath sign

informing walkers that it is 102m to the Brokken Bridge.

Clapham tries hard to be perfect. The natural valley of

Clapham Beck has been transformed with alien species

to provide a parkland stroll; the old village of Clapham

was redesigned by the Farrer family; St James’s Church,

which lists vicars back to 1160, was rebuilt in 1814 by the

Farrers; and now Clapham Beck runs from the waterfall

outlet of the lake through the village under several

unreasonably pretty bridges. Clapham’s tourist leaflet

lists the various attractions and services but does not

mention the Clapham-based Cave Rescue Organisation,

presumably not wishing to alarm tourists.

Two kilometres south of Clapham, a tributary from

the east joins Clapham Beck, which now becomes called

the River Wenning. This tributary has been formed 1km

east by the merger of Austwick Beck (from the north),

Fen Beck (from the east) and Kettles Beck (from the

south).

The Farrer family are largely responsible for the

attractiveness that we see today in Clapham.

Oliver Farrer, a rich lawyer, bought the estate in the

early 19th century. His two nephews, James and Oliver, re-planned the estate, including the building of the tunnels and

the replacement of much of the old village. They created

the drive and in 1837 opened Ingleborough Cave, the first

show cave in the region. It is apparent that Clapham Beck

used to flow through Ingleborough Cave. Today, visitors

may explore the floodlit passages for 1km underground to

see the 300m-year-old stalagmites and stalactites.

Reginald Farrer (1880-1920) was a botanist and

plant collector, particularly of exotic species from Asia,

many of which he introduced to Europe and especially

to the Clapham estate. He was also a painter and novelist

but he is most remembered for his botanical books, such

as The Garden of Asia, Alpines and Bog Plants, and My

Rock Garden. His name has been given to many of the

plants he introduced, such as gentiana farreri. He died in

the mountains of Burma, where, as the Buddhist he had

become, he was buried.

The Farrer family still own much of the estate around

the parish of Clapham.

The Cave Rescue Organisation (CRO) is a charity run

by volunteers to provide a rescue service around the Three

Peaks region. The emphasis on cave rescue in the title

reflects its history and the fact that these incidents are the

most demanding in terms of time, expertise and equipment

but nowadays 80% of CRO’s call-outs are to non-caving

incidents.

In the seven years 2002-2008 the CRO was called out

to 342 incidents, which is nearly one a week. These can be

classified as: walker (150), caver (74), animal (51), climber

(14), runner (11), cyclist (8), and other (34). Many of these

incidents involved more than one person: for example, on

October 4th 2008, 44 cavers were rescued in four separate

call-outs. The ‘other’ includes a motley collection of

mishaps, involving a foolhardy diver off Thornton Force,

someone who fell out of a tree, the rescue of cars stuck

in mud on the Occupation Road, the investigation of

abandoned canoes, and so on.

To assess the severity of incidents we can further

classify them as: fatal/involving injury/becoming lost,

exhausted or trapped. The caving incidents are 5/21/48,

although this 5 includes a person who collapsed and died in

White Scar Caves. Climbing incidents (1/11/2) are usually

serious. Although injuries are usually minor, walking

incidents (10/82/58) seem worst in terms of fatalities. The

10 fatalities include 5 heart attacks, 3 falls over a rock face,

and 2 unspecified. (Don’t have nightmares: these incidents

are still rare.)

Austwick Beck

At the head of Crummackdale a sizable beck

emerges from a couple of gashes in the fell-side.

This is called Austwick Beck Head but we are alert to

this situation now. The beck emerges after percolating

through the limestone fells above it and reaching the

impermeable lower layer at this level. The OS map

shows becks flowing off Simon Fell in this direction

only to disappear into potholes such as Juniper Gulf.

Tests show that this water emerges several days later at

Austwick Beck Head.

Austwick Beck Head is in an amphitheatre

surrounded by limestone scars. Its sheltered setting and

supply of fresh water no doubt encouraged the medieval

or earlier settlements, traces of which can still be seen.

Documents of the 13th century show that farming was at

that time active in Crummackdale. It is entirely livestock

farming now but this has only been so since the essentials

of life (bread and beer) could be transported from

elsewhere. There was arable farming in Crummackdale

until the 19th century.

Opposite Crummack farm on Studrigg Scar is a

clear geological unconformity, with Silurian slates at 60

degrees below horizontal beds of limestone. The cliffs

on the eastern edge of Crummackdale rim the extensive

limestone plateau of Moughton, from which there are

splendid views of Pen-y-Ghent. The flora of Moughton

is surprising, for there are shrubs of juniper and heather.

The juniper is a rare remnant of the woodlands that

covered the region thousands of years ago. Heather does

not grow on soil derived from limestone but somehow

here sufficient soil has become raised high enough not to

receive the alkaline water draining from the limestone.

In the past the heather must have attracted enough

grouse to encourage the construction of shooting butts,

an unusual feature on limestone terraces.

Studrigg Scar

Ingleborough from Moughton

Moughton

Careful study of the OS map reveals lines of grouse

butts on the southern and eastern slopes of Ingleborough.

Careful study on the ground reveals nothing much:

the butts were last used many decades ago and have

merged into their surroundings. The Farrers had bought

the Ingleborough manor as a shooting estate, the peaty

slopes being heather covered at that time. However,

over-grazing by sheep long ago removed all the heather

apart from a few remnants such as that on Moughton.

Before exploring Moughton, ensure that you are

fully familiar with a way off because it is surrounded

by quarries, steep cliffs and high walls. In the north the

footpath that runs from Crummackdale past Moughton

Scars is safe. In the south a high stile can be seen on

the horizon from the path that leads north from Wharfe.

However, it is in a state of disrepair, so it may be wise to

check before relying on it to get off Moughton.

Wharfe is a community of a dozen or so houses,

the owners of which have agreed not to waste money on

surfaced roads or exterior paint. So the cottages lie along

narrow, stony tracks and are of grey stone that seems at

one with the cliffs behind.

Left: Robin Proctor’s Scar and Norber

Left: Robin Proctor’s Scar and Norber

Right: A Norber erratic

Across the valley from Wharfe lie the famous Norber

erratics. These are so well known that few people today

will reach these fields completely unprepared for the

sight of dark boulders scattered incongruously on white

limestone but the number and size of the boulders will

surely astonish anyone. Their presence here must have

been a great mystery, until it was all explained to us.

As is now described in many textbooks, Ice Age

glaciers transported the boulders here from the Silurian

slate that underlies Austwick Beck Head and outcrops in

Crummackdale. The highest boulders now lie at about

340m. Austwick Beck Head is at 280m. The immense

forces at work during the Ice Age are indicated by the

fact that these huge boulders were lifted not just along

but also up the valley.

When the ice melted, the Silurian slate boulders

were left above the younger Carboniferous limestone

rocks. As we know, the latter is eroded by rainwater but

here the limestone under the boulders has been protected

and, as a result, many boulders are now perched on

pedestals above the general level. The height of the

pedestals (about 50cm) is a measure of the erosion since

the Ice Age.

[Update: I have since read that the boulders were not

transported as far along the valley as I thought, and hardly up at all.

Also, experts now believe that the rather satisfying explanation for the pedestals is

not the full story.]

Below the erratics are Nappa Scars, with another

example of unconformity, and the cliff-face of Robin

Proctor’s Scar, a name that demands an explanation.

There are several but they have in common the legend

that one Robin Proctor rode his horse over the precipice

to their deaths – a small price to pay to have one’s name

immortalised in full on Ordnance Survey maps.

These cliffs and those behind Wharfe, together

with the various ridges and contortions in the fields

of Crummackdale, tell us that this was a geologically

active area long ago – long before the Norber erratics

coincidentally added further geological interest. This

is the line of the North Craven Fault that we met at

Thornton Force above Ingleton. After the Silurian period

the layers of sandstone were crumpled and subsequently

eroded to leave steeply bedded, folded strata that are

now exposed in places. After the Carboniferous period

the area was raised above sea level with the greatest and

most irregular movements along the Craven Faults.

Walk 18: Crummackdale and the Norber Erratics

Map: OL2 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: By Austwick Bridge (769683) or elsewhere in Austwick.

This walk takes in many of the visible geological features of Crummackdale and also provides fine views of limestone

scenery.

Walk north through Austwick past a school to Town Head Lane on the left. 300m up the lane, before the last house on the

right, take the footpath through its garden. Across three fields you meet up again with Crummack Lane, which you cross to head

west for Nappa Scars. You can then stroll through the Norber erratics, heading for the stile in the northern corner (766703). From

the stile make your way north 2km along the indistinct ridge of Thwaite, which provides a good view of Ingleborough, to the

prominent cairn at Long Scar. From there take the clear path that runs to Sulber Gate, 1.5km northeast, with views of Pen-y-Ghent. Two hundred years ago this path was part of the Lancaster to Newcastle coach road.

Follow the path south over Thieves Moss to the fine Beggar’s Stile and then walk past ancient settlements and Crummack

farm and, 1km on from the farm, turn left to the ford and clapper bridge (that is, a bridge using long slabs of local rock) over

Austwick Beck at Wash Dub, where the sheep used to be cleansed. The unconformities on Studrigg Scar are visible from the track

from Crummack farm but for a closer look detour briefly up the track north from Wash Dub.

From the bridge follow the track 1km southeast to Wharfe. Continue through Wharfe to the road and then after a few metres

take the path right that leads over a footbridge and ford. Turn west, above the Wharfe Gill Sike waterfall, which deserves full

marks for effort, producing a fine cascade from only a trickle, and then by Jop Ridding to Wood Lane and back to Austwick

Bridge.

There is much to see on this walk and if you wish to take your time over it you might prefer to split the walk in two and do

the western half one day and the eastern half (including Moughton) on another day.

Short walk variation: Follow the long walk as far as the cairn on Long Scar. Then turn east to drop down to the farm of Crummack.

From there follow the track and Crummack Lane for 4km south to Austwick.

Austwick Beck passes the ancient village of

Austwick, the old core of which is surrounded by modern

houses, indicating that a legendary practice failed to

achieve its purpose. According to tradition, the residents

of Austwick used to pretend to be simpletons in order to

discourage outsiders from moving in. Harry Speight’s

Craven Highlands (1895) gives several examples of

Austwickian stupidity – but with no suggestion that this

was feigned. Today, Austwick revels in its reputation as

the ‘Cuckoo Town’. It would do better to revel in the

magnificent scenery with which it has been blessed.

There are man-made, as well as geological,

features to be seen in the landscape. Across the beck

from Austwick, Oxenber Wood is pockmarked with

old quarries, and common rights still permit Austwick

parishioners to gather stones there. Oxenber Wood and

the adjacent Wharfe Wood are old wood pastures that

are CRoW land. The dominant trees are

ash and hazel, with some hawthorn and

rowan, and, at the northern end, birch and

holly. The ground flora includes various

herbs such as wild thyme, salad burnet,

dog’s mercury and wood sorrel.

Also visible, especially in a low sun,

to the west and east of Austwick are the

stripes of ancient strip lynchets. These

are terraces up to 10m wide that were

created by Anglo-Saxons from the 7th

century onwards as they ploughed along

contours. These are the first lynchets we

have met and indicate how far west the

Anglo-Saxons colonised. Sometimes the

characteristic stone walls of the Dales

cross the lynchets, telling us that the

former are younger. Originally, a farmer

owned several strips of land but they

were distributed about different fields

in order to be fair to all. The need to

improve efficiency led to the creation of

individually owned enclosures, in a complex process

that began informally in the 12th century and became

enforced by parliamentary acts in the 18th century. The

stone walls were built to delimit the enclosures.

Below Austwick, Austwick Beck passes the old

and new Harden Bridge, a name that reminds us of

Austwick’s weaving industry that survived until the

late 19th century, harden being a kind of coarse linen

made from the hard parts of flax. By Harden Bridge is a

campsite that uses buildings that until the 1980s formed

an isolation hospital for people with infectious diseases.

The Top 10 dales in Loyne

1. Crummackdale

2. Dentdale

3. Kingsdale

4. Roeburndale

5. Barbondale

6. Grisedale

7. Whernside

8. Bretherdale

9. Littledale

10. Bowderdale

(Does Chapel-le-Dale count as a dale?)

Fen Beck

Fen Beck arises on the easternmost edges of Loyne,

around Feizor and Lawkland. In this gently

undulating land below limestone scars the watershed is

uncertain. Some houses in Feizor used to be considered

to be in the parishes of Clapham and Giggleswick (on

the Ribble) in alternate years. Feizor itself is an out-of-the-way hamlet, nestled neatly under the cliffs of Pot

Scar, a favourite with climbers. Southwest of Feizor is

the Yorkshire Dales Falconry and Wildlife Conservation

Centre, established in 1991 to help preserve birds of

prey.

[Update: The Falconry Centre was closed in about 2016.

Through some oversight, the Centre had continued to operate although its licence had lapsed.

An application for a 'new' licence was presumably refused. The site is now occupied

by the Courtyard Dairy, a cheese shop and café.]

Left: Lawkland Hall

Left: Lawkland Hall

Right: Eldroth Chapel

The parish of Lawkland is even more of a backwater.

The main route from York to Lancaster used to pass by

Lawkland Hall but the parish now lies anonymously

between the busy A65 and the less busy Leeds-Lancaster railway line. The oldest part of the Grade I

listed Lawkland Hall is 16th century, and much folklore

surrounds the hall’s peel tower and priest hole. From

the 16th century until 1914 the renowned Ingleby family

of Ripley, Yorkshire owned the hall. The Inglebys also

acquired the manor of Austwick and Clapham. Arthur

Ingleby rebuilt the hall in 1679 and when he died in 1701

left money, apart from to dependents, for a schoolmaster

and three poor scholars at Eldroth Chapel. Overall,

though, it seems that the Catholic Inglebys preferred to

keep a low profile, to which Lawkland is well suited.

Somehow it seems appropriate that the central

feature of Lawkland is the extensive peat land of

Austwick and Lawkland Mosses, a Site of Special

Scientific Interest. This now rare form of habitat was

once much more common, as indicated by the many

place names with “moss” in them. Lowland bogs are

peat lands that have developed over thousands of years

under waterlogged conditions. Over time, the surface

of the peat, formed by plant debris, is raised above the

groundwater level, resulting in a ‘raised mire’. Typically,

they are gently domed, but here peat cutting has obscured

this impression.

From a distance Austwick Moss is seen as an island

of ancient trees and scrub surrounded by pastures. It is

also an island of CRoW land, inaccessible by public

footpath, which is just as well because it is difficult, wet,

tussocky walking. The conditions support many bog

mosses and, in drier parts, birch woodland and fenland.

Various wading birds, such as lapwing, redshank, reed

bunting and snipe, and rare insects, such as the small

pearl-bordered fritillary butterfly, find a home there. It’s

good to know it’s there, for the benefit of the birds and

insects, but, in truth, it’s a damp, desolate place of little

appeal to most of us.

Kettles Beck

Left: A Kettlesbeck welcome for visitors: a stile on the

public footpath near East Kettlesbeck, with eye-level barbed wire

Left: A Kettlesbeck welcome for visitors: a stile on the

public footpath near East Kettlesbeck, with eye-level barbed wire

Right: Knotteranum

Kettles Beck is the first of many becks that we will

meet that flow north off the Bowland Fells and that,

because they flow over millstone grit, slate and sandstone

covered with glacial till, have a different character to

the becks of the mainly limestone Yorkshire Dales. At

first, the marked contrast between the dry whiteness of

the Dales and the muddy darkness of Bowland rather

depresses the spirits.

Bowland valleys tend to be deeply eroded, with fast-flowing becks tumbling through rocky channels over

small waterfalls. Trees have largely been cleared although

patches of ancient woodland remain in some steep-sided

valleys and there are a few conifer plantations, such as

Brow Side Plantation by Kettles Beck. The valleys are

rural, with verdant, rolling fields for cattle and sheep.

Population is sparse, being scattered in small villages

and isolated farmsteads, the latter being evenly but

thinly distributed, although many are no longer actively

farming. The buildings are usually of local gritstone,

adding to the sombre greyness, particularly in winter.

The farms are situated by flowing water and there is

often evidence, in the form of old millraces, weirs, and

so on, that it has been harnessed to power mills. There

are few hamlets above the main rivers of the Wenning

and Hindburn, and the lanes are narrow and winding,

with only two crossing the dark, bleak watershed to

Slaidburn.

The valley farmsteads are sheltered compared to

the windy, open higher fells. The fells are of heather

and grass, generally boggy and with few walls. The

high fells will be discussed further when we reach the

highest points of Bowland, but Kettles Beck itself arises

at the not very high but impressively knobbly peaks of

Bowland Knotts (430m) and Knotteranum (405m), on

the Lancashire – North Yorkshire border. The ridge is

one of the finest gritstone outcrops in Bowland, with

great jumbles of huge rocks, enabling a good scramble

for those venturing a brief walk from the road at the

watershed.

Kettles Beck runs 6km south from the boggy ground

of Austwick Common through farmland that has not

inspired the locals in their farm names: there’s a High,

East, New and Low Kettlesbeck (although Israel Farm

is more intriguing). It doesn’t inspire me much either

although walking down beside Kettles Beck one can

look wistfully across to Ingleborough.

The Wenning from Kettles Beck ...

The Wenning runs east, being first joined by Crook

Beck, which runs from Newby Moor on the southern

slopes of Ingleborough through Newby Cote and Newby

and across the rough ground of Newby Moss. This

extensive area of common land is now a Site of Special

Scientific Interest, noted for its purple moor-grass,

mosses and fens. There are also breeding birds such as

curlew, lapwing, redshank and snipe and a population

of the small pearl-bordered fritillary that perhaps flutters

between here and Lawkland Moss.

Walk 19: Ingleborough and Gaping Gill

Map: OL2 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: At Newby Cote (732705), where there is space for one or two cars; otherwise by the green in Newby (727701).

None of the four well-worn routes up Ingleborough (from Ingleton, Clapham, Horton and Chapel-le-Dale) provides a

satisfactory loop walk. I prefer to walk from Newby Cote on a grassy path from which we saw the new millennium dawn.

Follow the track north, through the gate and by the wall to the open fell. Bear slightly left. After ten minutes or so Little

Ingleborough comes into view. Pick up the broad green path up it. From Little Ingleborough the beaten track to Ingleborough is

obvious. After a tour of the summit plateau, take the clear path east (part of the Three Peaks route). Note the Fell Beck spring (the

source of the Wenning) close by the path. After 1km cross a stile but after a further 1km don’t cross a second stile - instead, follow

the wall south at the foot of The Allotment. A path just above the limestone terrace runs 10m or so west of the wall.

A fence will be seen partially enclosing Juniper Cave. Juniper Gulf, into which falls water that becomes Austwick Beck,

is just above it. There’s a series of potholes, dangerous and difficult to find – don’t bother, as they do not compare with what’s

ahead. Keep near the wall. Eventually, a wall comes to it at right angles, leaving a gap. Don’t go through the gap but follow the

wall right and then left. A stile will be seen just ahead. Cross it and continue due west, which brings you to the unmistakable

chasm of Gaping Gill.

Take the path south (which leads to Clapham) and when a stile comes into view after about 150m bear half right. There are

many vague paths here but basically keep west of the wall, between the shakeholes, until, after 2km, as the wall swings south,

you see ahead the gap between the green pastures by which you gained access to the moor. Cut across the dry Cote Gill and

thence to Newby Cote.

Short walk variation: Follow the long walk as far as Little Ingleborough. (Continue to Ingleborough only if it is irresistible.) Turn

south east and follow the path to Gaping Gill. Continue, as for the long walk, back to Newby Cote.

The green hillocks that rise to 200m running west

from Clapham towards Bentham and Ingleton are fields

of drumlins created by glacial ice sheets flowing off the

hills of the Yorkshire Dales. The oval-shaped contours

on the map indicate the east to west trend of the glaciers.

The gentle slopes of the drumlins and their rich boulder

clay soil provided good sites for settlement and farming

from prehistoric times, which is shown in the increasing

occurrence of the Old English -ham, -ber and -ton in place

names. The grazed pastures are divided into irregular

patterns by stone walls and hedgerows, reflecting their

origins as pre-medieval fields rather than the later, more

systematic, enclosures of the higher fells.

The now well-established Wenning passes under

Clapham Viaduct, which, unlike earlier viaducts,

has no aesthetic merit. The viaduct carries the Leeds-Lancaster railway line. The original plan was to build

the Lowgill-Clapham line via Ingleton first but work on

this was suspended and instead the branch to Lancaster,

completed in 1850, became the main line, with the

Lowgill line eventually completed in 1861. The line to

Wennington runs down the Wenning valley, naturally

without all the meanders of the river, which it crosses

seven times in all.

Just beyond the viaduct the Wenning is joined

by Jack Beck, which runs past Jack Beck House,

where painting courses are run by the painter Norma

Stephenson. I like her description of her modus operandi

for producing her semi-abstract pastels of the northern

fells: “dissatisfaction sets in ... almost always ... because

the painting has become too explicit. Radical measures

are required ... I will often dribble water into the pastel,

causing rivulets and textured effects, or I will sweep my

hand across the surface to remove detail.” I have tried

this with the creation you are reading, to no great benefit,

alas. I conclude that it is not a work of art.

Beyond the new Skew Bridge, Keasden Beck joins

the Wenning.

Keasden Beck

Our journey has taken us to many hidden and unknown

becks but compared to Keasden Beck they are all

gaudily extrovert. Nobody seems ever to have written

a good or bad word about Keasden Beck. There are

no postcards of Keasdendale (in fact, I may have just

invented ‘Keasdendale’). In the 4km from Gregson’s

Hill to Turnerford Bridge there are no footpaths in the

valley or across it. There is no road in the valley: all

the farmsteads are reached by private tracks from the

Clapham to Bowland Knotts road.

Keasdendale

Left: Bowland Knotts

Left: Bowland Knotts

However, now that all of Burn Moor above the

pastures has been made CRoW land we can at least gain

a long distance view into this secretive valley. Burn

Moor is tough going: all heather, grass tussocks and bog.

When it was restricted to grouse shooting Burn Moor

was called the ‘forbidden moor’: now, ‘forbidding’

would be a better word. There is a good path on springy

peat (in summer) along the ridge from Bowland Knotts

to Great Harlow (486m) and over Thistle Hill, but

elsewhere walking is a struggle. Should your eye catch

upon Ravens Castle and Raven’s Castle on the map,

be warned that there are no castles, although there are

ravens. And yet there is compensation up here. The

silence is complete, apart from birds such as skylark,

curlew and merlin, and the view of the Three Peaks is

much better than from the road, from where Whernside

is rather obscured by Ingleborough.

Right: The ‘Standard on Burn Moor’ boundary stone, marked on OS maps

Right: The ‘Standard on Burn Moor’ boundary stone, marked on OS maps

The most striking feature on an aerial photograph

of Burn Moor is the large stripes of different shades of

green. At first glance they look like the fairways of golf

courses. They are in fact the result of burning practices

and remind us that the fells are far from natural, despite

their familiar appearance.

After the last Ice Age the hills became covered with

broadleaved woodland, which was cleared from about

3000 BC. Peat then formed from decaying vegetation on

the gentle slopes and hilltops, so creating blanket bog.

We use words like ‘bog’, ‘heath’ and ‘marsh’ informally

but scientists need precise definitions. For them, ‘blanket

bog’ is peat deeper than 50cm (even if it is dry). Less

deep peat is ‘heath’ if there is at least 25% cover of

small shrub heather-like plants; otherwise it is ‘marsh’

or ‘marshy grassland’. It all gets more complicated,

as there are different types of bog, heath and marsh,

depending on altitude, slope, hydrology, geology, and

so on. Although the vast areas of Bowland’s bogs and

heaths may seem ample, they are actually rare in global

terms and, because of the threat to the Bowland Fells,

are priority habitats in the UK’s Biodiversity Action

Plan.

Keasden Beck gathers all the water that flows east

and north from the Burn Moor watershed, which here

forms the county border. Like all Bowland becks, it cuts

through hard millstone grit, occasionally exposing layers

of underlying sandstone and shale.

After a hidden run through the valley, Keasden

Beck emerges at Turnerford by Keasden Moor. This

insignificant-looking moor is a Site of Special Scientific

Interest, for being, according to its citation, “the only

known site for the marsh gentian Gentiana pneumonanthe

in the Yorkshire Dales” – which is quite something

considering that it is not even in the Yorkshire Dales.

The small pond in the middle of the moor is surrounded

by common marsh-bedstraw, sneezewort and lesser

skullcap (the names, at least, are fun).

By the moor are St Matthew’s Church and a

telephone box, which together constitute the hub of the

scattered village of Keasden. The church has a fine view

across to Ingleborough but, like most of Keasden, makes

little attempt to compete with the beauty of the Dales

hills. The peat brown Keasden Beck runs past various

farmsteads, some converted, some not. Clapham Wood

Hall is a rather sad cottage on the site of a much grander

hall that was demolished in the 19th century.

Until 1800 it was the home of the Faraday family,

from which came the eminent scientist Michael

Faraday (1791-1867), although Keasden cannot

claim him, as he was born in London after his

father had moved away from Keasden in 1780.

After a further 1km Keasden Beck joins the

Wenning by Hardacre Wood.

The threat to the Bowland Fells takes various forms:

draining, pollution, burning, over-grazing and the presence

of humans.

Land drainage for agricultural purposes is so

damaging to the ecology of bogs and heaths that very few

new hill drains have been allowed recently. Existing drains

remain a problem, as they lower the water table and lead to

shrinkage of the peat and increased fire risk.

As blanket bogs receive all their nutrients from the

atmosphere, they are very sensitive to air pollution. The

pollution provides too much nutrient and the increased

growth threatens more sensitive species.

Perhaps the most important factor is the practice of

rotational strip burning, which has been carried on for

centuries. First, it must been conceded that the practice

is necessary if the hills are to be conserved in something

like their present state, because if left to nature they would

revert to scrub and woodland. The controlled burning of

strips of heather every few years produces areas of heather

of different age and hence height and structure.

In recent years, the intention has been to provide

suitable habitats for grouse, although farmers may also

burn heather to produce young shoots for sheep to graze

and so spread the sheep more evenly over the fells. Either

way, there are benefits to many other species that depend

upon healthy moorland. Overall, the management of grouse

moors has helped retain the habitat but today the numbers

of grouse are in decline.

We must also acknowledge the threat to this sensitive

environment from increased human access, encouraged

by the Countryside and Rights of Way Act. We can now

wander where we will but the plants do not appreciate

walkers’ boots and neither do nesting birds. If horse-riders,

mountain-bikes, motorbikes and off-road vehicles were

allowed, would the fells survive?

[Update: At the time I wrote this I had been taken in by

landowners' and grouse-shooters' guff about the benefits of heather burning.

The practice damages peat and releases carbon. It should be banned, as it now is on some

moors of England. Before there is a complete ban, perhaps the practice will die out anyway when

the already fragile grouse-shooting industry becomes unviable as rich shooters

increasingly find other ways to spend their money than making themselves social pariahs and

figures of ridicule, as the general public

becomes more aware of what grouse-shooting entails.]

The work of the Keasden mole-catcher

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Gretadale and a little more Lunesdale)

The Next Chapter (Wenningdale, Hindburndale and Roeburndale)

© John Self, Drakkar Press

Right: Gaping Gill

Right: Gaping Gill

Left: Trow Gill

Left: Trow Gill

Left: Robin Proctor’s Scar and Norber

Left: Robin Proctor’s Scar and Norber

Left: Lawkland Hall

Left: Lawkland Hall

Left: A Kettlesbeck welcome for visitors: a stile on the

public footpath near East Kettlesbeck, with eye-level barbed wire

Left: A Kettlesbeck welcome for visitors: a stile on the

public footpath near East Kettlesbeck, with eye-level barbed wire

Left: Bowland Knotts

Left: Bowland Knotts

Right: The ‘Standard on Burn Moor’ boundary stone, marked on OS maps

Right: The ‘Standard on Burn Moor’ boundary stone, marked on OS maps