The Land of the Lune

Chapter 11: Wenningdale, Hindburndale and Roeburndale

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (The Wenning Headwaters)

The Next Chapter (The Lune Floodplain and the Top of Bowland)

Upper Roeburndale

The Wenning from Keasden Beck ...

Right: Mewith Head Hall

Right: Mewith Head Hall

The Wenning runs by the Forest of Mewith, below

the northern slopes of Burn Moor. Mewith is

an area of undulating farmland, with scattered

farmsteads, isolated woodlands, many paths and tracks,

and no discernible pattern. It is crossed by many becks

that flow off Burn Moor, where the county border runs

northwest past the Queen of Fairies Chair and the Great

Stone of Fourstones. The former is notable only for its

name but the latter is a remarkable 4m-high monolith,

from which there is a good view across to the Three

Peaks.

Left: Great Stone of Fourstones

Left: Great Stone of Fourstones

The Wenning flows calmly between banks

of alder, with birds such as common sandpiper,

dipper and grey wagtail, although sadly there are

few of the sea trout for which the river was once

known, partly because so many alien rainbow

trout have escaped from a trout farm. The river

reaches High Bentham and, shortly after, Low

Bentham, which is older but now smaller. High

Bentham expanded north, south and east and

Low Bentham expanded north, south, and west

but recently they have taken tentative steps along

the B6480 towards one another. I will consider

this dumbbell shape to be Bentham.

Its leaflet for tourists begins with the sentence

“Bentham is not a tourist centre”, which must

be welcome news for those staying at the large

caravan park. Bentham was once more positive,

for it had pioneered the idea of a holiday camp,

long before Butlin and Pontin. From 1908 to

1925 a tented village was set up on the banks of

the Wenning for holidaymakers: single men on

the north bank, everyone else on the south bank,

with a suspension bridge in between.

Bentham considers itself a market town

and shopping centre with an industrial heritage.

It appeared as Benetain in the Domesday Book

and was granted a market charter in 1306. High

Bentham Mill, using a millrace from the Wenning

near Bentham Bridge, was established in 1750,

possibly on the site of an old corn mill. It later

worked in tandem with Low Mill (built 1785), mainly

spinning flax. By 1795 the mills were importing Baltic

flax to make sailcloths. The owner in 1814, Hornby

Roughsedge, bought Bentham House, which no longer

exists, and the manorial rights to Ingleton.

It was Mr Roughsedge who had funded the ill-fated

hospice on Ingleborough (mentioned in Chapter 8). His

benefaction was more gratefully received in Bentham,

where he paid for St Margaret’s Church (Margaret

coincidentally being Mrs Roughsedge’s name), built in

1837 on a hill that now overlooks the unstylish Bentham

Bridge, which replaced one washed away in 1964.

Right: The Wenning between High and Low Bentham

Right: The Wenning between High and Low Bentham

The mills were bought in 1877 by Benson

Ford to manufacture silk. The Ford family

were Quakers and their enlightened views

on the treatment of employees enhanced

the significant Quaker influence upon the

region. Quakerism had been strong since

the 1650s, with the Calf Cop meetinghouse

being established in 1718. The Quakers have

generally had a disproportionate influence on

Loyne’s society and commerce, to which they

directed their energy and enterprise as their

religious views barred them from professional

and political careers.

The mills once employed up to 800

people and were the dominant factor in village

life until they closed in 1970. One derivative

company, Angus Fire (now called Kiddes),

based on an invention to weave tubes to make

fire hoses, still operates but now on a site

across the railway line, the original mill site

having been converted for small businesses

and residences.

Before the 19th century, Bentham was unusual

in having no wealthy gentry to build large mansions.

There are some rows of 17th century cottages and

Collingwood Terrace has an intriguing conception. In

1726 the will of William Collingwood of York provided

for “the maintenance and support of six old decayed

housekeepers in [Bentham], men and women, six of

each sex”. I don’t know why he was so grateful to the

housekeepers of Bentham. According to its plaque, we

owe the continued existence of the terrace to a Mrs

Titterington, who provided funds in 1900 to restore the

houses as bungalows.

To the west of Bentham, the Wenning is joined by

Eskew Beck, which begins life as County Beck near the

Great Stone of Fourstones. Eskew Beck is important for

its exposures of Carboniferous rocks with rare fossils.

The county border is along County Beck and Eskew

Beck and then continues west along the Wenning. The

greater importance of county borders in earlier times,

when, for example, fugitives could escape the law by

crossing them, is reflected in the history of Robert Hall,

just to the south. It was built in the 16th century for the

Cansfield family, who, as recusant Catholics, needed

hiding places and escape routes.

To the southwest of Robert Hall is a moor that has

miraculously escaped the notice of man until recently,

for it has never been ploughed or drained. Consequently,

this is a Site of Special Scientific Interest for being

“the only extensive example of species-rich undrained

and unimproved base-flushed neutral grassland in

Lancashire”, including several rare plant communities.

To the non-specialist, it gives an idea of what would be

the natural state of this drumlin scenery.

Left: The remains of the engine house of Clintsfield coal mine

Left: The remains of the engine house of Clintsfield coal mine

In contrast, to the north at Clintsfield the signs of

human activity are evident, with the only significant

remains of the local coal mining industry. The old

engine house, which operated until about 1840 and was

later converted to a dwelling, and its adjoining square

chimney still stand, more or less, and traces of the ten or

more coal pits marked on old maps are still visible.

Above Clintsfield is The Blands, which was gutted

by fire in 2009. All the old farmsteads of Loyne, with the

intertwined families and colourful characters that lived

in them, have interesting histories but surely none can

match that of The Blands, once the home of Perpetual Arthur.

Just to the west, four pipes cross above the railway

line. This is the continuation of the Haweswater

Aqueduct, which we saw crossing the Lune near Kirkby

Lonsdale. The pipes go under the Wenning and then up

and over the railway. The aqueduct is gravity-fed (that is,

there are no pumps) but it is clearly not downhill all the

way. It is a single 2m pipe along most of its length but

is split into four smaller cast-iron pipes to cross rivers

and valleys.

Right: Wennington Hall

Right: Wennington Hall

Shortly after, the Wenning reaches its eponymous

village, Wennington, a triangle of houses around a green

bisected by the B6480. Its appearance has been improved

by the restoration of the old Foster’s Arms Hotel, empty

for many years. Wennington Hall, now a school, lies to

the north. It was re-designed in a Tudor-Gothic style

by Edward Paley in 1855. A notice at the gate informs

us of its history, including the fact that a motto of the

Morley family (who owned the hall from 1330 to 1678)

is inscribed in the headmaster’s study: “S’ils te mordent,

mord les” – ‘if they bite you, bite them’, which I trust

hasn’t been adopted as the school motto.

[Update: Wennington Hall closed as a school in 2022.

There are plans for it to be converted into a hotel.]

At Wennington, the dismantled railway line to

Lancaster and the still-existing line to Carnforth separate,

with the Wenning continuing beside the former. It passes

under the large Tatham Bridge, which can be barely seen

from the road. It has five arches, including one for the

railway, which it therefore does not pre-date. The line

opened in 1849 and for the first six months ran from

Lancaster only as far as a temporary Tatham Station,

just beyond the bridge. The bridge provides access to the

neat St James the Less Church, on a site where a church

is thought to have existed since Saxon times.

Perpetual Arthur was the nickname of Arthur Burrow

(1759-1827), who owned The Blands from 1787. This

relatively uneducated but multi-talented man became a

local legend for his many activities: blacksmith by trade, he

mined coal surreptitiously under The Blands, an entrance

to the shaft being conveniently close by the fireside; he

knew the bible better than many theologians, after being

taught to read in one night by an angel (according to him);

he built mysterious niches in his sunken garden, possibly

to intrigue gullible antiquarians; he distilled liquor; he ran

plum fairs; and he fathered thirteen children.

But the activity by which he was best known was his

unceasing quest to develop a perpetual motion machine, an

endeavour that attracted the interest of eminent engineers of

the day. Arthur would talk eloquently, enthusiastically and

at great length on his ideas for perpetual motion (and on the

bible, for that matter) if given half a chance. This was, of

course, in the early days of the Industrial Revolution, when

self-taught engineers were rapidly developing new forms

of power from coal and water. He redirected the nearby

beck to run under his house, which may have helped to

sustain the illusion of perpetual motion.

The History of the Parish of Tunstall considers that

“he had a touch of genius which, had his education been

sufficiently good, might have ranked him among the

world’s great men.” No doubt, if he had actually invented

a perpetual motion machine then he wouldn’t be all but

forgotten today.

The Wenning at Wennington

East of Tatham Hall on a small hill by Tatham Park

Wood are various mounds

and ditches that look like the

remains of old settlements,

although they are not marked

as such on maps. According

to old maps, there were

many coal pits (Moorhead

Pits) to the east. The nearby

Netherwood Hall is much too

trim to retain its old name of

Bottom.

Below Hornby Park

Wood the River Hindburn

joins the Wenning.

The River Hindburn

By the time it reaches Botton Bridge the River

Hindburn is already a considerable size, having

gathered up all the becks that drain Greenbank Fell,

Botton Head Fell and Whitray Fell below the semi-circular ridge that runs to the ancient Cross of Greet

(which is no longer a cross but a large boulder with a

socket in which a cross may once have stood). This is

a vast area of peat bogs and heather, turning to grass

tussocks lower down. It is all CRoW land but walking

here is more of a challenge than a pleasure. In winter,

there are only grouse for company. From the ridge there

are broad views of Pendle and the southern Bowland

Fells and to the north Whernside looks particularly noble

(Ingleborough always does). The alignment of the ridges

– Ingleborough, Whernside, Gragareth, and Middleton

Fell – shows clearly that they all belong to Loyne.

Looking towards the Three Peaks from White Hill

Right: The tower on White Hill

Right: The tower on White Hill

There is a rough path from the Cross of Greet to the

highest point of the ridge, White Hill (544m), but it has

few visitors, most of whom are puzzled by the tower

that stands near the trig point. It’s about 4m high, with a

notch in the top. It is in fact the middle of three towers

in a line, the other two being 500m north and south. The

other two cannot be seen when standing at the middle

one but if you walk to them you will see the notch of the

middle one back on the horizon.

If you have followed the narrative carefully, you

may suspect an answer to the puzzle. I think they are

sighting pillars used for surveying the Haweswater

Aqueduct, which we last saw near Wennington. If we

extrapolate the line of the towers on an OS map then

we find “air vents” marked on the exact line 3kms in

both directions. The towers seem to mark the line of the

aqueduct below our feet as we stand on White Hill. It

is a surprising thought, in the bleak emptiness of White

Hill, but the aqueduct must cross the Bowland Fells

somewhere and it certainly doesn’t go over them.

Other than the towers, there is no trace of this

engineering feat on the ground but if we plod over to

Round Hill on Botton Head Fell we may visit a much

older engineering construction that is (just about) visible.

We have passed many Roman roads on our journey but

have always had to take the expert’s word for it. Here

we might be able to convince ourselves that the slightly

raised ridge that runs between Goodman Syke and Dale

Beck is the line of a Roman road. It is actually more

convincing to view from a distance, for example, from

the footpath between Botton Bridge and Botton Head.

This is the Roman road that we have tracked from Over

Burrow past Low Bentham and that is now heading for

Ribchester.

Just above Botton Mill there is a permissive path that

enables access to Summersgill Fell. Here, at the parish

boundary fence, the nearest visible road or building is

far distant: ideal for those allergic to humanity or fond

of nude fell-walking (or, especially, both). A walk here

in spring is not, however, in silence: agitated lapwings,

curlews and grouse will attempt to distract you from

their nests.

Left: Feathermire in Tatham

Left: Feathermire in Tatham

Once off the open fell we are among the lush green

pastures of the several farmsteads in the upper Hindburn

valley. Apart from the intrusive conifer plantation at

Higher Thrushgill, the map looks unchanged from a

century or two ago, and moreover most of the farmsteads

are still farmsteads, unlike most dales we have visited,

where many are derelict or converted into residences

and holiday cottages. There is an appealing timelessness

here, with the farms going about their business, nestled

below the rough fell and with open views across to

Ingleborough and the Lake District.

In contrast to nearby Keasdendale, the Hindburn

valley is crossed by many footpaths, which, to judge

from the curiosity of the sheep, are not often used. The

Hindburn passes below the quiet village of Lowgill,

a gathering of a score or so cottages on the line of the

Roman road. There’s also a primary school for about

forty pupils, some of whom must travel

far to get here and understandably so for

the school is known for the quality of

education provided. The only other public

building seems to be the Wesleyan Chapel

of 1866. To the north, above Mill Bridge,

is the older (but rebuilt in 1888) and more

impressive Church of the Good Shepherd,

a fitting name for this rural area.

education provided. The only other public

building seems to be the Wesleyan Chapel

of 1866. To the north, above Mill Bridge,

is the older (but rebuilt in 1888) and more

impressive Church of the Good Shepherd,

a fitting name for this rural area.

Right: River Hindburn near Mill Houses

To the south of Lowgill, at Ivah Great

Hill, a new woodland of native trees

was created in 2003 by the community

group Treesponsibility’s nifty scheme of

engaging local people in tree-planting, to

help slow global warming. We, or at least

those who planted trees, are welcome to

visit to see the trees growing.

Three kilometres below Lowgill,

the Hindburn passes under a bridge built

in 1840 and carved with the name of

Furnessford Bridge, although the 1847 OS map calls

it Furnaceford Bridge. Below the bridge there are no

footpaths by the Hindburn, which is a pity as it runs

prettily by steep cliffs over minor waterfalls. I hardly

need to say what Mill Houses used to be but I ought

to mention the nearby meadow on the footpath from

Clear Beck Bridge. This meadow is too small to have

been affected by modern agriculture and as a result is

a Site of Special Scientific Interest for being “one of

the best examples of species-rich meadow grassland in

Lancashire”. It is so rich, in fact, that over 130 species

have been recorded.

Clear Beck joins the Hindburn after Hindburn

Bridge, running from Clearbeck House, which has

a garden with follies, sculptures, a lake, and views of

Ingleborough. The house is one of about twenty studios

on the Lunesdale Studio Trail, in which local artists open

their studios each summer to enable visitors to see their

work in paintings, textiles, prints, sculptures, mosaics,

jewellery, ceramics, drawings and photography.

Below Wray Bridge, the River Hindburn and the

River Roeburn come together, as nature intends.

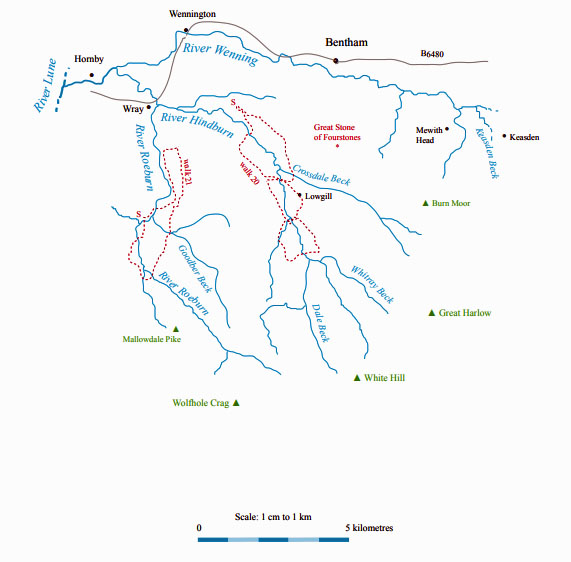

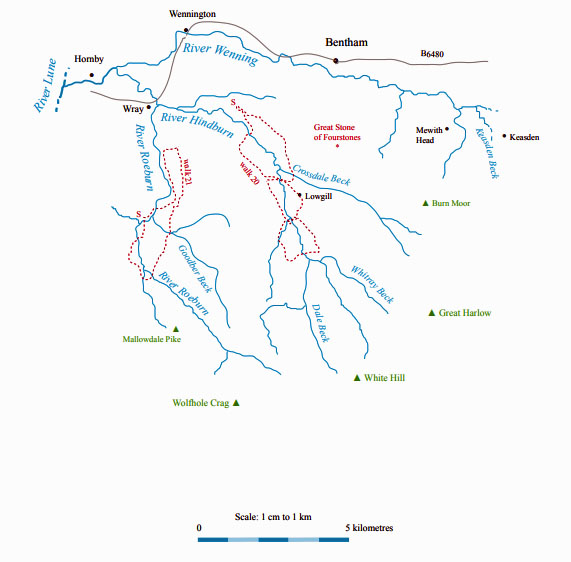

Walk 20: Middle Hindburndale and Lowgill

Map: OL41 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: A large lay-by east of Ridges on the Wray to Low Bentham back road (633679).

Walks in the upper Hindburn do not compare with other high-level walks I’ve suggested: it is better to stroll through the

farmsteads of the middle Hindburn around Lowgill.

This walk uses four bridges over the Hindburn to make a route of three loops. There is some walking on roads but they are

generally quiet. Careful use of the OS map is needed, to locate about fifty stiles or gates.

Take the path that starts on the drive to Ridges and skirts around Riggs Farm next to it, continuing on the path south and

then southeast (diverted through a wood) to the Furnessford Road. Over Furnessford Bridge take the path past the barn and up a

fine old track through the wood to Birks Farm, dated 1667. The four large manholes seen here and by Riggs Farm mark the line

of the Haweswater Aqueduct. Follow the road southeast past Park House and take the track to Lower Houses. Turn left and after

0.5km drop down east by a wooded gully to a footbridge over the Hindburn.

Head south across an open field to the barn seen ahead. Then walk up through the wood behind it and across the fields,

heading for Lowgill School. Walk south through Lowgill to High Ivah (along the line of the Roman road), and drop down

southwest across the field to Stairend Bridge. Continue on the road past Botton Mill. After 1km turn left through Lower Thrushgill,

continuing east to walk across a field and down to a footbridge. Continue for 0.5km to join the bridleway through Swans (0.5km

north) and back to Stairend Bridge.

Walk 100m to the road corner again and this time take the path north, by the Hindburn. Follow this path for 2km past a few

derelict barns back to the wooded gully, and drop to the footbridge again. Over it, this time turn left through a wood and up to the

road near Mill Bridge, 1km east. Turn left and cross the bridge and, after an optional detour to the Church of the Good Shepherd,

continue on the road north for 2.5km to Spen Lodge. Beware of traffic as you contemplate the views of distant hills.

Beyond Spen Lodge take the footpath through Little Plantation if it is not too overgrown – otherwise continue on the road

and turn left onto Furnessford Road. Take the path west below Trimble Hall to rejoin the path from Ridges.

Short walk variation: Clearly, using only three, two or one of the bridges will shorten the walk. However, parking in the valley

is not easy although there is space on the corner near the track to Swans (655640). The best of the short walks is the loop south

from there through Lower Thrushgill and Swans, combined, if you have time, with a loop north to Over Houses Great Wood and

back through Lowgill.

The River Roeburn

We were once accosted by a friendly couple in

Roeburndale who felt that they had discovered

the best place in England and often journeyed over

from Blackpool to savour it. They were pleased, not

disappointed, to find others who shared their secret. The

view from the brow of the road after passing Thornbush

is enchanting: to the alpine-like green pastures down by

the woods up to the conical peak of Mallowdale Pike

and beyond, with the Three Peaks arrayed on the left.

And Roeburndale encompasses both the ancient and the

new, as we’ll see.

The River Roeburn rises at the old Yorkshire-Lancashire county border below Wolfhole Crag (527m)

and Salter Fell. This is open fell country, far from any

road and therefore likely to be deserted. It was not always

so, for Hornby Road (or the Old Salt Road) was once an

important route and in its southern part coincides with

the Roman road that came up Round Hill from Lowgill.

Hornby Road, with the head of Roeburndale to the right

Left: Wolfhole Crag

Left: Wolfhole Crag

It is possible that the CRoW policy will give a

new lease of life to Hornby Road. The track, which is

unusable by cars, provides an excellent

walking surface, although distances are

long and any loop off-track involves

strenuous going. Walking north, the

view that opens up at Alderstone Bank

is remarkable, with a long-distance

180° horizon from Black Combe to

Ingleborough. The track marked on

OS maps as going to a shooting cabin

on Mallowdale Fell now continues

over the ridge to join the track from

Tarnbrook Fell. It may therefore be

used to reach the ridge path to Ward’s

Stone but there will be awkward bogs

around Brown Syke after wet weather.

[Update: Recent OS maps show the new track over the

watershed and a number of other new tracks on the Bowland hills. Grouse-shooters must be getting lazier.]

If you walk up here you will

become aware of the screeching gulls

that nest on Mallowdale Fell and

Tarnbrook Fell. These are a relatively

new phenomenon, first being reported

in 1936. There are now over 25,000

pairs nesting annually, forming

England’s largest inland colony of

lesser black-backed gulls. Thousands

more are culled to avoid possible bacterial contamination

of the Lancaster water supply.

[Update: There aren't over 25,000 gulls now.

The saga of the lesser black-backed gulls on Bowland

is convoluted. In short, the land-owners continued to kill the gulls even though it became illegal,

with the authorities renewing the licence either through error or by turning a blind eye.

When the licence was eventually ended, killing continued, on and off, despite the

threat of legal action. The gulls are not really killed because they pollute our water -

they are killed because they get in the way of grouse. There seems to be some kind of stand-off at the moment, perhaps

because the legal status of the gulls' protection is unclear now that we are no longer

a member of the EU.]

Hornby Road is a recommended route for mountain

bikers, who are (at the moment) not allowed on the

increasing numbers of tracks on the Bowland Fells

proper. It is also part of the 45km North Lancashire

Bridleway, opened in 2004. This runs from Denny Beck,

Halton via Roeburndale to Chipping. Let us hope that

the few residents in these remote areas benefit from,

rather than resent, these new activities.

On Mallowdale Pike there is a memorial cairn to one

Anthony Mason-Hornby (1931-1994). The cairn gives

no explanation for its presence here. The area was out

of bounds to the public until the CRoW Act took effect

in 2004. Very few walkers will take advantage of the

opportunity to venture here but even so it is a regrettably

growing practice for private grief to impose upon special

places, without good reason.

Right: The Irish bridge below Middle Salter

Right: The Irish bridge below Middle Salter

[Update: This so-called Irish bridge has been replaced.

It is hoped that fish can now move up-river, whereas before they could not pass

through the narrow pipes.]

At Mallowdale the Roeburn leaves the open fell

to run through woods past Lower Salter to be joined

by Bladder Stone Beck (what a charming name) and

Goodber Beck, which runs in a deep ravine from the

empty grasslands of Goodber Common. Even the most

desolate areas have their uses. The large heath butterfly,

one of only two English butterflies that are on the

European list of threatened species, breeds here. Hare’s

tail cotton grass, its main larval food plant, flourishes on

the Common.

The Roeburn runs through 5km of Roeburndale

Woods, one of the most extensive deciduous woodlands

in Lancashire, which is perhaps not saying much as it one

of the least wooded counties of England. These woods

provided an enclave for the red squirrel (until recently:

I have heard no recent reports of red squirrels here). A

permissive path in Outhwaite Wood enables us to see as

we walk north the gradations of tree types, reflecting the

changes of soil, from lime, birch, hazel and alder to ash,

elm and oak.

In a clearing opposite Outhwaite Wood is the Middle

Wood environmental centre. This was established in

1984 to “advance, research and provide education for the

public benefit in those techniques of farming, forestry,

wildlife and countryside management, building, energy

utilisation and human lifestyle, which are in tune with

the natural cycle and which do not upset the long term

ecological balance.” Quite foresighted, then, and today a

range of ecological buildings for sustainable development

can be seen. The study centre uses solar panels and a

wood-burning stove for heat and is powered by wind

power. The community yurt (a Mongolian circular tent)

is the main meeting place. Whenever I pass through

only a few wisps of smoke at most seem to disturb the

air of away-from-it-all self-sufficiency. After years of

apparently anonymous inactivity, the centre is now so

vigorously advertising its facilities (courses, website,

shop, study centre, rural classroom, camping barn) that

it is in danger of becoming mainstream.

The Top 10 body-parts in Loyne

1. Bladder Stone Beck, Roeburndale

2. Bosom Wood, Cautley

3. Backside Beck, east Howgills

4. High Stephen’s Head, near Ward’s Stone

5. Fleshbeck, below Old Town

6. Rotten Bottom, Dentdale

7. Heartside Plantation, Middleton Fell

8. Hand Lake, north Howgills

9. Long Tongue, Cockerham Sands

10. Bone Hill, near Pilling

From left to right, Gragareth, Whernside, Ingleborough and Pen-y-Ghent from above Middle Wood,

not forgetting the clouds

As the Roeburn nears the village of Wray it is joined

by Hunt’s Gill Beck, which runs past Smeer Hall. Here

the last coal pit in the region closed in 1896. On the

Roeburn’s right bank is a line of cottages associated

with the old Wray Mill. Like many mills we have

passed, it dates back centuries and went through many

incarnations (cotton, wool, bobbins, silk, and so on) in a

valiant attempt to survive, before finally succumbing in

the 20th century.

Just after the mill cottages, the Roeburn passes

under Kitten Bridge, the first of three bridges in Wray,

the others being Wray Bridge over the Roeburn and

Meal Bank Bridge over the Hindburn. The first and last

were washed away in the notorious flood of August 1967

and have since been replaced. Wray Bridge survived but

perhaps it would have been better if it hadn’t, because

the logs and debris piled up against the bridge, causing

the torrent to back up and demolish a number of cottages.

Luckily, there were no casualties but 37 people were

made homeless. The event is commemorated in a garden

close by Wray Bridge.

Some of the cottages washed away used to be the

homes of various Wray artisans, because from about

1700 to 1850 Wray was a veritable hive of industry.

Apart from the mill and local mining and quarrying,

Wray was known for the production of hats, nails, clogs

and baskets. It is unclear why Wray in particular became

an industrial centre but no doubt once it began to build

a reputation it was enhanced by other workers being

attracted to the area for employment. The industries

were relatively short-lived and Wray has since relaxed

into a quiet, commuting community.

Walk 21: Roeburndale

Map: OL41 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: Just north of the cattle grid north of Barkin Bridge (601638).

This walk gives a tour of middle Roeburndale, with views up to the wilderness of upper Roeburndale. It first makes use of

a new permissive path to and through Outhwaite Wood. This path is not marked on OS maps but there are clear signs to follow,

the first being by a stile a few metres northwest of the cattle grid. The footpath sign is a symbol of a deer: I hope that encouraging

us to look for them doesn’t scare them away.

The path crosses two fields and then drops down (rather muddily) to cross a new footbridge to the east bank. There are good

views at times of the Roeburn below. The path continues just outside the wood, which it eventually enters. It then joins a loop

walk within Outhwaite Wood. Take the lower path of the loop (it isn’t necessary to cross the swing bridge to the camping barn, but

it’s fun to do so (twice)). After 1km the path emerges below the wood and joins the public footpath that has crossed the footbridge

from Middle Wood. Continue north and then east up the path into fields.

Follow the footpath until it nearly reaches the road and then turn right, following the path for 3km above Outhwaite farm,

past Wray Wood Moor, and all the way to Harterbeck, where Goodber Beck forms an impressive waterfall. Cut southwest across

fields for 1km to reach High Salter, where Hornby Road ceases to be a road.

Drop down behind High Salter, cross Mallowdale Bridge, and after Mallowdale farm cross a footbridge to enter Melling

Wood. This path climbs up to give good views down into secluded Mallow Gill. At Haylot Farm take the paved road down to the

bridge across the Roeburn. Pass Lower Salter, with its tiny Methodist church, and return to Barkin Bridge.

The map shows other footpaths that may be used to shorten (or lengthen) the walk but avoid the one shown crossing

Goodber Beck in Park House Wood: a safe crossing point is hard to find and anyway slippage has made the path unusable. A stile

linking Bowskill Wood and CRoW land (at 611646) enables many variations on our route.

Short walk variation: Any short walk is, of course, constrained by the need to find bridges to cross the various rivers and becks.

One possibility is to follow the long walk as far as the footbridge to Middle Wood and to then cross the bridge and walk via Back

Farm and the road back to Barkin Bridge. Another possibility is to complete the southern half of the long walk, that is, to walk

south from Barkin Bridge, east through Lower Salter to the waterfall at Harterbeck and then follow the long walk from there.

A walk up the Main Street from Wray Bridge reveals

some of this history. First impressions suggest that Wray

is different from other Loyne villages. The grey, stone

buildings and converted farms and cottages are familiar

but they are set back from the road, with cobbled areas

in front. By Loyne standards, Wray is a new village, as

it is not listed in the Domesday Book. It was designed, if

that is not too bold a term, by the then Lord of Hornby in

the 13th century for his farm workers. The farm buildings

were set out on the wide street, with a village green at

the north end.

All except one of the farms have been converted into

residences but the original forms can still be discerned.

Overall, if Main Street were without its multitude of

parked cars then it would have a picturesque quality of

bygone times. The green, however, no longer exists, as

the B6480 was built across it. With the original road,

now called The Gars, it has made an island of Wray

House and a few other houses.

Despite its youth, Wray seems proud of its age:

almost every house bears a datestone, usually of the 17th

century, even one built in the 20th century. One of the

first houses met on the walk up Main Street from Wray

Bridge is that of Richard Pooley, or Captain Richard

Pooley as he insisted on being called. He flourished in

the Civil War and returned to the family home in Wray

to bequeath £200 a year to establish a primary school

in 1684. A plaque on the school wall confirms this; a

second asserts that “Bryan Holme (1776-1856) founder

of the Law Society was at school here” (there should

be an “a” before “founder”, as he did not do so alone).

The school is, unusually, not a church school, possibly

because it pre-dates local churches: Holy Trinity Church

was built in 1840 and the Methodist Chapel in 1867.

Anyone interested in rural architecture will enjoy a

stroll along Main Street. But not on May Bank Holidays,

for then the village and the roads around are jammed

for the Wray Fair, featuring the celebrated Scarecrow

Festival. The festival is part of an ancient springtime

ritual, passed down through generations of Wray

residents, dating all the way back to … 1996. The idea

was copied from a village in the Pyrenees in an attempt

to promote the Wray Fair. It succeeded beyond anyone’s

hopes and now tens of thousands visit, mainly to see the

scarecrows. Rather ironically, if that is your intention

then it is better to avoid the fair itself, as the scarecrows

adorn the village in the days before the fair, to the

distraction of unsuspecting passing motorists. Those

industrious workers of the 18th century, striving to make

a bare living, would be bemused by the feverish activity

of today’s villagers, as they strive to out-scarecrow one

another.

Beyond Wray Bridge the Roeburn joins the

Hindburn, which continues uneventfully for 2km to join

the Wenning.

The Wenning from the Hindburn

The Wenning swings south below Hornby Castle, a

prominent landmark of the lower Lune valley. The

Earl of Montbegon was granted the Hornby estate after

the Norman Conquest and was no doubt based at Castle

Stede by the Lune at first. At some time the village was

relocated, with a castle being built on the present site in

the 13th century. By the early 16th century the manor was

in the hands of Sir Edward Stanley, or Lord Monteagle

as he became after bravery at Flodden. It was the 4th

Lord Monteagle who received the warning letter about

the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Actually, the letter advised

him to stay away from Parliament, which may suggest

that the plotters considered him to be a sympathetic

friend.

As a Royalist stronghold the castle was besieged

during the Civil War but for some reason was not

demolished after capture as it was supposed to be. In

time, however, all of the castle except the central tower

fell into ruin and has been replaced. Despite appearances,

the present structure is mainly of the second half of the

19th century, when it was remodelled in the Gothic style,

complete with battlements. The castle can be viewed

from Tatham or from the Lune valley with Ingleborough

behind or, at closer quarters, from Hornby Bridge, with

the lawns sweeping down from the castle.

Hornby Castle and the Wenning

The castle’s structures are echoed in the octagonal

tower of St Margaret’s Church, built by the 1st Lord

Monteagle. It is probably on the site of an older church,

as it houses several ancient stones and crosses, one,

the ‘loaves and fishes’ cross, probably being pre-Norman. Opposite St Margaret’s is the Catholic Church

of St Mary, built in 1820, with the presbytery nearby,

where the noted historian John Lingard lived. By the

presbytery is indubitably the oldest bus stop in England,

with a datestone of 1629.

The two Grade I listed buildings (the castle and St

Margaret’s) set standards that the rest of Hornby does

well to live up to, which it does via a further 26 Grade

II listed structures. The main street has a number of fine

sandstone buildings and the institute has recently been

refurbished at a cost of £1.3m. Unfortunately, the Castle

Hotel, an old coaching inn, is letting the side down by

remaining boarded up and looking increasingly derelict.

The quiet residential tone reflects the fact that

Hornby, despite the market charter granted in 1292,

never developed any significant industrial activity,

unlike nearby Wray. In fact, its market town status had

lapsed by the 19th century.

The Wennington-Lancaster railway line ran to the

south of Hornby, enabling a short-lived livestock market.

Nearby is an interesting building built in 1872 by the

Lunesdale Poor Law Union as a workhouse for the poor

of 22 parishes. As with many other buildings, it has been

redeveloped for residential use.

I once sat for some time by the Wenning Bridge

in Hornby watching a heron attempting to swallow an

eel longer than itself - longer than its neck, at least.

It managed, somehow. There is concern about the

declining number of eels in the Lune, as in most British

rivers. I don’t think the heron is to blame. As with the

salmon, causes may be man-made (the various barriers

we have built to the eels’ migration up the rivers) and

natural (infections with parasites). DEFRA’s 2008

Eel Management Plan for the North West River Basin

District is on the case.

As the Wenning approaches the Lune it runs in a

much straighter line than in earlier times, with old river

channels visible on the south bank. Looking back from

the Lune, the Wenning points directly to its source on the

eastern flanks of Ingleborough.

John Lingard (1771-1851) is a rarity in Loyne – someone

who achieved eminence through activities within the

region. The plaque at the presbytery reads “Home of Dr

John Lingard, Catholic priest and historian, 1811-1851”,

which needs careful interpretation. The dates are those for

which the presbytery was Dr Lingard’s home, not those of

Dr Lingard himself. The Catholic Encyclopedia says that

he “retired to Hornby” in 1811 and refers to the “fruits of

his leisure there”. It is a little unclear, therefore, how active

he was as a Catholic priest in Hornby.

The ambiguity in “Catholic priest and historian”

is probably deliberate, for a key question is whether Dr

Lingard was a Catholic historian or a historian. He wrote

his eight-volume The History of England whilst living in

Hornby, the last volume appearing in 1830. The history was

later re-published in ten and then thirteen volumes. This

monumental work is important because, firstly, it provided

a comprehensive account of English history that has been

respected ever since it was first published and, secondly,

his methodology of not relying upon general opinion but of

going back to primary sources helped to change the nature

of historical research.

Inevitably, that general opinion did not always agree

with Lingard’s interpretations but he was always able

to refer back to his sources. Nowadays, we would not

expect the dispassionate objectivity that Lingard sought.

It is hardly surprising that his most controversial sections

concerned the Reformation, for he was, after all, a Catholic.

Nor that he was virtually ignored by academia but revered

by Catholics, so much so that it is thought that he was made

cardinal in petto (that is, in secret, to be announced later)

by Pope Leo XII.

Hornby Castle and Ingleborough

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (The Wenning Headwaters)

The Next Chapter (The Lune Floodplain and the Top of Bowland)

© John Self

Right: Mewith Head Hall

Right: Mewith Head Hall

Left: Great Stone of Fourstones

Left: Great Stone of Fourstones

Right: The Wenning between High and Low Bentham

Right: The Wenning between High and Low Bentham

Left: The remains of the engine house of Clintsfield coal mine

Left: The remains of the engine house of Clintsfield coal mine

Right: Wennington Hall

Right: Wennington Hall

Right: The tower on White Hill

Right: The tower on White Hill

Left: Feathermire in Tatham

Left: Feathermire in Tatham

education provided. The only other public

building seems to be the Wesleyan Chapel

of 1866. To the north, above Mill Bridge,

is the older (but rebuilt in 1888) and more

impressive Church of the Good Shepherd,

a fitting name for this rural area.

education provided. The only other public

building seems to be the Wesleyan Chapel

of 1866. To the north, above Mill Bridge,

is the older (but rebuilt in 1888) and more

impressive Church of the Good Shepherd,

a fitting name for this rural area.

Left: Wolfhole Crag

Left: Wolfhole Crag

Right: The Irish bridge below Middle Salter

Right: The Irish bridge below Middle Salter