The Land of the Lune

Chapter 14: The Salt Marshes

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (The Lune to Lancaster)

The Next Chapter (Into Morecambe Bay)

Bazil Point, Overton

The Lune from Lancaster ...

Beyond Carlisle Bridge the Lune swings south

and takes on a different character - in fact, two

characters and all shades in between. If the tide

is out and there is little water flowing down the Lune,

it is a gentle, low river, with sandy, or at least lightly

muddy, beaches, providing long, flat views. If the tide is

in and the Lune is flowing high, then it becomes a wide,

raging river, threatening flood defences.

These conditions give rise to the characteristic

coastal salt marshes of the lower Lune. The marshes

form from marine alluvium deposited in sheltered areas

that are covered only by occasional high tides. Aldcliffe

Marsh, Heaton Marsh, Colloway Marsh, Lades Marsh

and Glasson Marsh continue for 6km, on both banks of

the Lune, down to Morecambe Bay. There’s an esoteric

appeal to these remote, simple, almost primeval,

landscapes, often aglow under the setting sun. The land

is naturally flat and open, heavily fissured with creeks,

and littered with the debris of high tides and floods. If

grazed the marshes are a close-cut, deep green; if not,

they are in summer full of colourful flowers such as

thrift and sea asters.

Right: The Lune at the Golden Ball

Right: The Lune at the Golden Ball

The Lune passes Salt Ayre, which, like Green Ayre

upriver, used to be an island (the parish boundary, which

presumably follows the old course of the river, runs

through Salt Ayre). It is now a sizable hill, of which

the good citizens of Lancaster and Morecambe may be

proud – it is created from their rubbish. Beyond Salt

Ayre is the Golden Ball pub, facing the detritus left by

tidal waters. It is known as ‘Snatchems’ because of the

legend that passing ships short of crewmembers would

grab inebriated drinkers from the pub, a tradition that

has sadly lapsed. A similar custom would be welcome

for the modern pest, the jet-skiers who are increasingly

ruining the calm of the Lune estuary, now that they are

no longer allowed on Windermere.

Left: Aldcliffe Marsh, looking towards the Lakeland hills

Left: Aldcliffe Marsh, looking towards the Lakeland hills

The salt marshes require peace – not for us,

because the winding creeks and glutinous mud make

this dangerous territory, but for the thousands of birds

that gather here. There are no buildings on the marshes

and the isolation and, ideally, tranquillity make this fine

feeding and roosting ground for many wildfowl and

wading birds, such as Bewick’s swans, little egrets,

ringed plovers and spotted redshanks.

Right: Two lines of pylons from Heysham Power Station

marching over the old breakwaters on the Lune

Right: Two lines of pylons from Heysham Power Station

marching over the old breakwaters on the Lune

Inland of the salt marshes are low coastal drumlins.

They are oval-shaped, aligned north to south, indicating

the direction of glacial flow. The scattered farmsteads

are sited on the gentle slopes above the poorly drained

pastures, with the few trees bent by the prevailing wind.

The whole peninsula south of Morecambe reaches no

higher than Colloway Hill (36m). Inland of the low

Heaton-Colloway ridge is a wide, flat expanse, formerly

of bogs and mosses but now reclaimed pasture, with

many ditches lined with rushes. Seawaters have no doubt

inundated the area in the past. Today, it is traversed by

power lines from the nuclear power station and by the

A683 to Heysham, for people travelling to the many

caravan parks nestling by the power station.

On the east bank, the land rises to the old village of

Aldcliffe, which has managed to remain detached from

Lancaster. It has not, however, managed to retain its old

hall, once known as the Hall of the Catholic Virgins. In

the 17th century Aldcliffe Hall was the property of ten

sisters of Thomas Dalton of Thurnham, who was killed

at Newbury fighting for Charles I. Seven of them were

convicted of recusancy in 1640 and much of their estate

sequestered (this, as mentioned in the previous chapter,

was the period when Catholic priests were being

executed in Lancaster). After the restoration of Charles

II, two of the sisters felt bold enough in 1674 to set up a

stone inscription saying (in Latin) “Catholic virgins are

we; even with time we disdain to change.” They were

too bold, it transpired, for after the Jacobite Rebellion

of 1715 the government enquired into all estates held by

Catholics and duly confiscated Aldcliffe Hall, considering

that it was “given to Popish and superstitious uses”.

The hall, or rather its replacement built in 1817,

was demolished in 1960. The land is now occupied

by peaceful suburbia. It would not, however, still be

peaceful if the 1998 proposal for a western bypass from

the M6 at Hampson Green across the Lune to Heysham

had been approved. The road would have passed within

200m of Aldcliffe. Residents argued that a northern

bypass would be better but, in the end, they were saved

more by the bats and great crested newts, both European

protected species.

Along the Lune the flat horizons are broken only

by the tall pylons from Heysham Power Station. If these

should seem alien to you it might help to recall the words

of Stephen Spender in his 1933 poem ‘The Pylons’, a

poem that heralded a new school of poets, the Pylon

Poets, who used technological imagery as themes. He

wrote “... Pylons, those pillars bare like nude giant girls

that have no secret ...”. Nude girls?! - I think I prefer to

continue to see them as eyesores.

The ridge between the Lune and the A6 continues

south, past the old village of Stodday, where the wooded

gardens of the secluded Lunecliffe Hall (formerly

Stodday Lodge) were said to have Roman remains, to

its highest point at Burrow Heights (59m), below which

Burrow Beck runs to the Lune.

Burrow Beck

Left: The Jessie Ashton Memorial

Left: The Jessie Ashton Memorial

We followed the Roman road down the Lune valley,

from the Fairmile Road near Tebay, past Over

Burrow, by the assumed road that ran past the milestone

found at Caton, and on to the fort at Lancaster. Fine

place though it is, Lancaster is unlikely to have been the

Romans’ final destination. Common sense tells us that,

in addition to the high road we met crossing the Bowland

Fells above Lowgill, there would be a road heading

south on the low coastal plains. And remembering Low

Borrowbridge and Over Burrow, the name of Burrow

Beck, flowing around Burrow Heights, will raise our

suspicions.

Sure enough, aerial photographs indicate an old

road to the east of the trig point on Burrow Heights,

leading towards the Roman road known to pass east

of Garstang, heading for Ribchester. More tangibly,

four carved figures and two pillars were found near

Burrow Heights in the late 18th and early 19th century.

The pillars are usually described as milestones although

they are half the height of the Caton milestone and their

inscriptions only honour the emperor, without giving

distances anywhere.

Other finds confirm that a road set off from Lancaster

along the line of what is now Penny Street. Evidence

is still being uncovered. In 2005 a memorial plaque or

headstone, over 1m square, was found north of the canal

by Aldcliffe Road. The inscription is to Insus, son of

Vodullus, and the stone depicts a soldier on horseback

above a kneeling, decapitated man. The Lancaster

Roman Cavalry Tombstone, as it is now called, is on

display in Lancaster City Museum

Burrow Beck runs quietly for 7km from just east

of the Ashton Memorial in Williamson Park through

Bowerham and Scotforth, the southern suburbs of

Lancaster, to Ashton Hall by the Lune. The memorial

and the park were given to Lancaster by, and named

after, the industrialist, James Williamson, later Lord

Ashton. When ennobled in 1895, he named himself

after the manor of Ashton, where he had bought the

hall in 1884. He also gave to Lancaster the Town Hall

and the Victoria Monument, with a mural of Victorian

worthies, including his father. All this, together with

his high-profile roles as Liberal MP, High Sheriff, town

councillor, justice of the peace, and so on, might suggest

that he was no shrinking violet but he was apparently

a very private man. He did not allow any portraits of

himself in the Town Hall: the imposing one that now

stands at the top of the main stairway was added later.

Williamson Park was created in 1881 from the old

Lancaster Moor quarry, stones from which had been used

to build most of Lancaster’s houses. The neo-classical

Ashton Memorial of 1909 is often described as a folly,

which my dictionary defines as “a building of strange

or fanciful shape, that has no particular purpose.” That

seems a slander on the designer (John Belcher) and a

slur to the second wife of Lord Ashton, for whom it

was intended as a memorial. If we called it the Jessie

Ashton Memorial then we wouldn’t mistake it for self-aggrandizement. It is said that the lady with whom

Lord Ashton took up after his wife’s death demurred

at such an ostentatious memorial to her

predecessor in the lord’s affections. The

plaque in the memorial merely says that

it is to the Ashton family.

Today, it is the most prominent

landmark in Lancaster, a proud symbol

to all who pass on the M6. However,

before it was restored in 1987, Lancaster

residents seemed to disown it. According

to the Lancaster City Museum exhibit,

Lord Ashton left Lancaster in high

dudgeon in 1911 to live at Lytham St

Anne’s. Writing to the local paper, he

said that some of his workforce had

become “disloyal and discontented” by

joining trade unions and voting Labour.

In return, the locals were content to let

the memorial (which they called ‘the

structure’) fall into decay, which it did.

Their attitude may have been coloured by

the fact that unlike most other industrial

philanthropists of the time he did not

provide any buildings of direct use to

his workers. He did, however, kindly

provide a footbridge by Carlisle Bridge

so that his Skerton workforce could get

to his factory.

Lord Ashton’s main home was

Ryelands House in Skerton rather

than the grand Ashton Hall. The hall

had been rebuilt in 1856 to retain a

tower probably of the 14th century. The

manor of Ashton was part of the lands

of Roger of Poitou until taken over by

the Lancaster family in 1102. Over the

centuries, the estate passed through the

hands of the Laurences, the Gerards,

the Gilberts, the Hamiltons, and the

Starkies, before reaching the Williamsons. The hall is

now the headquarters of Lancaster Golf Club.

Burrow Beck runs across the golf course, through

an ancient fishpond, into a lake, and under the old

Lancaster-Glasson railway line, completed in 1883,

before dribbling into the Lune. Lord Ashton had a

private railway station (Waterloo) at which trains could

be flagged down.

A further kilometre south the River Conder crosses

salt marsh into the Lune.

The Lune after Burrow Beck joins, with a fisherman trying a variant of the traditional method of haaf netting

The River Conder

Left: Baines Cragg

Left: Baines Cragg

Right: Across Cragg Wood from Baines Cragg

The River Conder arises at the Conder Head spring to

the north of Clougha and flows west through Cragg

Wood to the parish of Quernmore. The parish stretches

10km from Halton to Ellel and has long been settled.

Two Roman kilns have been found, one below Lythe

Brow Wood and the other near the village of Quernmore.

In medieval times, Quernmore was a hunting forest, at

one time in the charge of the Gernets of Halton and later

passing into the hands of the Duchy of Lancaster. It

was sold by the crown in 1630. The present Quernmore

Park Hall was built in 1794 by Thomas Harrison for the

Gibson family.

On Birk Bank there is a large three-arched bridge

over Ottergear Clough and two sturdy towers. The

function of these structures is unclear although they

presumably have something to do with the Thirlmere

Aqueduct. Below these slopes a few areas of reed bed,

a rare habitat for Loyne, are being restored, perhaps to

enable bearded tit and marsh harrier to breed.

The Conder merges with Mother Dyke, from near

Quernmore Park Hall, and passes the isolated St Peter’s

Church, built in 1834.

At Conder Mill, below the now

ornamental pond, it is joined by Rowton Brook, which

arises, properly enough, on Rowton Brook Fell on the

south flank of Clougha Pike (413m). Clougha Pike is not

really a peak, although it looks so from the southwest,

but is merely the end of the westerly ridge from Ward’s

Stone. Its position offers an extensive panorama

that includes, circling from the east: Ward’s Stone,

Hawthornthwaite Fell, Snowdon (on a very clear day),

Blackpool Tower, Morecambe Bay, the Isle of Man (on

a clear day), the Lakeland fells, the Howgills, Whernside

and Ingleborough. At closer quarters is a view of the

Lune valley, from its estuary up to the Lune Gorge in

the Howgills.

In 1851 it was proposed to use the waters of Rowton

Brook for a reservoir to supply water to Lancaster.

However, the city architect Edmund Sharpe asked, “why

… are we to drink the miserable storage of a dribbling

brook, four miles off, when we have at our very feet the

magnificent storage of the river Lune, through which a

whole river runs daily to change and purify it?” In the

end, it was decided, rather cheekily, to use the nearby

Grizedale Brook, which drains to the Wyre, for the

reservoir. The Lune was used much later.

To the north of Rowton Brook the jumbles of

millstone grit provide evidence of the quarrying of

querns that gave the region its name. In the fields you

may well see sheepdogs at work and, if not, you will

certainly hear them within Rooten Brook Farm, where

a dozen dogs are housed. These are no ordinary dogs

– they are the dogs of the champion sheepdog trialling

family, the Longtons. Tim Longton senior won the

English National in 1949 and his son, Tim junior, won

it five times from 1965. So renowned was the latter that

the first programme of the BBC’s One Man and his Dog,

explaining the nature of sheepdog trialling, was filmed

at Rooten Brook Farm. The fourth generation Longton,

Michael, won the English National in 2004 at the young

age of 24.

The Top 10 viewpoints in Loyne

1. Clougha Pike

2. Great Knoutberry Hill

3. Wild Boar Fell

4. Orton Scar

5. Ingleborough

6. Combe Top, Middleton Fell

7. Caton Moor

8. Hornby Road, Roeburndale

9. Whinfell Beacon

10. Brownthwaite Pike

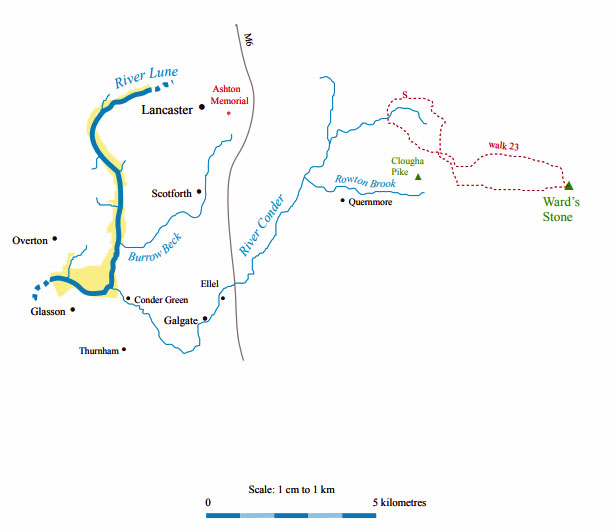

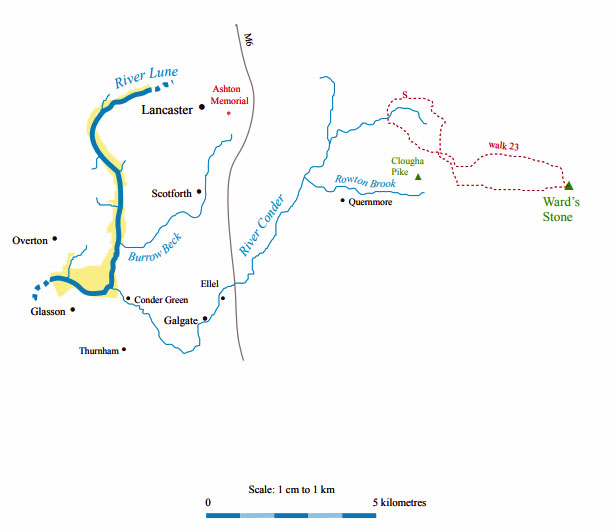

Walk 23: Ward’s Stone

Map: OL41 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: Near Little Cragg (546618).

There are three conditions for this walk: no closure of the access area for grouse shooting (this is allowed for up to 28 days

a year: ring 0845 100 3298 if you want to check), no dogs and (preferably) good visibility. With few features marked on the map,

I’ll give the OS grid reference for strategic points.

From Little Cragg Ward’s Stone can be seen 5.5km southeast on the horizon but a direct route would involve much scrambling

over heather and rocks. So set off in the opposite direction, west down the road, past Baines Cragg. After Bark Barn, climb a stile

on your left, walk south across the infant Conder on a permissive footpath and enter CRoW land (at 537613). Keep on the track.

After cairns on the right (at 541605), the track swings left and becomes less steep. With three cubic structures visible ahead, note

a small post just after a large rocky outcrop on the left (at 552596).

[Update: The small post has disappeared - but the large rocky outcrop is

still there!]

At a junction of tracks (at 560597), follow the sign pointing right. At the next side-track, not marked on OS maps (at about

562592), turn left, ignoring the sign pointing ahead. Initially the track heads direct to Ward’s Stone but it then curves left and then

right. As you approach the shooters’ hut (at about 585588), note Ward’s Stone to its right and imagine your route. Scramble up

behind the hut, aiming for a cone-shaped stone on the horizon, and proceed to Ward’s Stone.

[Update: The 'next side-track' referred to is marked

on recent OS maps.]

At Ward’s Stone the panorama is revealed, with the Three Peaks, the Lakeland fells, the Lune estuary, and your starting

(and finishing) point. Ward’s Stone (560m) is sadistic: after battling to the stone, you find that the official top, just 1m higher (the

highest point of the Bowland Fells), is at a second trig point, visible 1km away. Climb the stone to get 1m above the first trig

point and settle for that.

Head west on the ridge path and after 2km (at 565588) turn right at the track you meet. After a few minutes, ignore the track

off to the right – you went that way earlier. Ignore the second track to the right, as you did earlier. The cubes, with enigmatic

plinths, come into view to the left. Pass below the cubes and reach the rocky outcrop with the little post. (If you miss the post,

just continue back the way you came.) Turn right here (at 552596) on a path that heads towards the Caton Moor wind turbines.

Small posts mark the way but they are difficult to see. Some kind souls are creating cairns.

The path continues towards the wind turbines and then curves left. A wall is seen 50m to your right (at 551608): the Conder

Head spring is just to the left. Keep the wall to your right until a stile is seen ahead. Climb the stile, turn right by Sweet Beck and

walk past Skelbow Barn to Little Cragg.

Short walk variation: The obvious short walk is to follow the long walk as far as the small post (at 552596) and then turn left and

follow the last part of the long walk. A shorter walk is possible along a path that runs east south of Cragg Wood to cross the beck

from the Conder Head spring and on to Sweet Beck.

Right: Across Quernmore to Clougha

Right: Across Quernmore to Clougha

The village of Quernmore has only a converted

barn or two, a row of new dwellings by Rowton Brook

and a residence called Temperance House, dated 1826.

The temperance movement was at that time becoming

more powerful. Lancaster’s Temperance Society was

formed in 1833 and at one time Lancaster had twelve

temperance hotels.

As you follow Rowton Brook

west, you may be increasingly

overcome by the nauseous stench

from the mushroom farms near

Nether Lodge. In 2002 thirty-three

illegal immigrants were found

working here and deported. The

mushroom farms are an anomalous

presence in the Quernmore valley,

for it is a rich agricultural area that

seems wasted on mushroom sheds.

Conder Mill Bridge is only

wide enough for a stream 2m across.

Something seems awry here. The

Langthwaite ridge to the west rises

100m above the Conder and is 4km

from Clougha Pike. The valley seems far too broad and

deep for such a trickle. And indeed it is, for before the

Ice Age the Lune ran through this valley, until glacial

deposits blocked its path.

The engineers’ attempt to defy this process of

nature by laying a pipe through the Quernmore valley

to take water from the Lune to the Wyre was sadly

rebuffed by nature itself, when an explosion at the valve

house in Abbeystead in 1984 killed sixteen people.

The investigation found that the explosion was caused

by the ignition of methane but that “the likelihood of

a flammable atmosphere arising there had not been

envisaged” – which seems an oversight given the history

of coal mining in the area.

The Langthwaite ridge from Knots Wood to

Hazelrigg is formed from millstone grit overlain by

boulder clay and supports mixed farming and woodland.

It separates the coastal drumlin fields of Lancaster and

its surroundings from the glacial sands and clay drift

of Quernmore. As might be expected, communication

masts are prominent.

The River Conder runs through the fishery and

golf course of Forrest Hills, set up in 1996 and another

example of rural diversification, this time of the farm

of Banton House. It is now also a resource centre with

green credentials, part of the Bowland Sustainable

Tourism network, which (simplifying) is concerned with

attracting visitors to an area without spoiling it.

Below Forrest Hills the Conder crosses the Kit

Brow stepping stones, where, as for all Loyne’s becks,

the ‘trickle’ is not always so. Lancaster University holds

an annual race over the stepping stones, which one year

were far under water, and I became so as well when I

was washed away from the safety rope provided.

The Conder passes the small village of Ellel and

the larger one of Galgate. Galgate has the misfortune to

be bisected twice, by the A6 and the west coast main

line railway. Perhaps that serves it right, for having a

name proclaiming it to be the gate or road to Galloway.

The only building of note is the old mill, which is said

to be the first mechanical silk mill in England. It was

bought as a corn mill in 1792, converted to spin silk, and

operated until 1970. It now houses “the country’s largest

bathroom emporium” and various smaller units.

Left: Glasson Canal

Left: Glasson Canal

The marina on the Lancaster Canal is relatively

peaceful although the public moorings are busy on

summer weekends. Just south of here the canal begins

a branch to Glasson, completed in 1826 with six locks.

In the dry summer of 2006, the branch was closed

for periods because the water levels were too low –

which raises a question: where does canal water come

from? Lancaster Canal itself is supplied by Killington

Reservoir but for the Glasson branch most of its water is

taken from the River Conder, small as it is and as a result

even smaller than it should be.

The Conder runs slowly west, north of the canal,

passing Thurnham Mill, now the Mill Inn. The mill

operated using water from the canal, which is possible

only through being next to a lock. To the south is

Thurnham Hall, with an interesting history.

The usual pattern with the grand halls of Loyne is

that for centuries they provided a home for the family

at the apex of the local rural hierarchy; in the 18th or

19th century they may have been bought by a newly-rich industrialist; either way, the residents continued to

lead the gentrified country life until the middle of the

20th century when societal changes meant that the halls

had to be converted to some other use, such as offices,

a school or flats. Thurnham Hall followed this pattern,

with unhappy consequences.

Thurnham Hall was the manorial home from the

12th century and was bought by Robert Dalton in 1556.

The Daltons continued to buy land around Lancaster,

to become the largest landowner in the region. Dalton

Square and nearby streets in Lancaster are named after

members of the Dalton family. The Daltons were staunch

Catholics, as we saw with Aldcliffe Hall, and funded the

nearby Church of St Thomas and St Elizabeth, built in

1745. After the Daltons left in the mid 20th century, the

hall lapsed until it was restored in 1973, to be a classy

restaurant for a while.

It was then bought to form the centrepiece of a

timeshare operation, Thurnham Leisure Group, with

headquarters in Lancaster. Holiday courtyards and a

swimming pool were built around the hall. However,

amid rising complaints from customers, the Group

crashed in 2004 leaving a £5m debt. The managing

director, Fred Fogg, was given a two-year prison

sentence for conspiring to defraud finance companies.

Sunterra Europe, with a head office in Lancaster but part

of the US-based Sunterra company, acquired the hall

and other property, plus the irate customers, for £2m.

Sunterra Europe was put up for sale in 2006 and bought

by Diamond Resorts International for £350m. However,

the Diamond Resorts office on Caton Road seems

somewhat inactive (or empty: it is hard to tell without

peering through the darkened windows). Today it is an

unnerving experience to walk on the public footpath

amongst the possibly disgruntled holidaymakers of

Thurnham Hall Country Club. Perhaps the renowned

ghosts of Thurnham Hall are restless.

For its last kilometre the Conder is tidal, with the

nearby roads occasionally under water, especially the

one to Glasson, which was badly flooded in 2002. In the

tranquil meanders derelict craft fall and rise but seem

never to be resurrected. Above the flood level is the

Stork, a 17th century inn that has retained something of

its old character. By the viaduct for the old Lancaster-Glasson railway line is the Conder Green picnic site,

which is on the route of the 220km Lancashire Coastal

Way. The Conder Green salt marshes are not grazed and

as a result have a great variety of plants, including the

rare lax-flowered sea-lavender.

The Conder (three times) at the Stork, Conder Green

The Lune from the Conder ...

Left: Glasson marina

Left: Glasson marina

Right: Glasson Watch House

East of the Conder the Lune passes Glasson, which

is part port, part resort, but not much of either. On a

fine day, with a sea breeze gently fluttering the mastheads

in the marina, it makes a pleasant outing, although there

is not much to do or to see, apart from leisurely activity

about the boats. There is no beach or seaside promenade,

and only a few old-style catering establishments, with

two pubs.

A large barrier separates the Lune, and hence the

sea, from a dock that was completed in 1787 after the

Lancaster Port Commission resolved to build it for ships

unable to navigate the Lune to reach the new St George’s

Quay. Before then, the area was a marsh, with the farms

of Brows, Crook and Old Glasson to the south.

The dock did not flourish for long, against

competition from better docks at Preston and Fleetwood,

although the Glasson Group of companies is still an active

importer, especially of animal feedstuffs. Still standing

are the Custom House (which functioned from 1835 to

1924) and the Watch House (built 1836), which with

typical Loyne immodesty is claimed to be the smallest

lighthouse in England. A nearby dry dock for ship repair

functioned from 1841 to 1968, when it was filled in to

become an area for light industry. The Port of Lancaster

Smoke House, winner of the 2007 North West Fine Food

Producer of the Year award, is on the West Quay.

A further barrier separates the dock from the large

marina on the Glasson branch of the Lancaster Canal.

Commercial traffic ended long ago but canal-based

tourism is now Glasson’s main occupation. This it

supplements with other unassuming activities: an annual

folk-music festival; the racing of radio-controlled laser

boats in the marina; a weekend gathering point for

bikers.

Left: St Helen’s Church, Overton

Left: St Helen’s Church, Overton

The railway, arriving late (1883) and departing early

(1930 for passengers, 1964 for freight), left little trace in

Glasson, apart from Railway Place, a group of cottages

that pre-date the railway. The line of the track now forms

part of the Lancashire Coastal Way, which continues over

the barrier separating dock and marina, through Glasson,

and up Tithe Barn Hill, which at a magnificent height of

20m provides a fine view, often with excellent sunsets,

across the estuary to Overton and Sunderland, with the

Lakeland hills beyond. There’s a 360º view-indicator

and five benches, all facing Heysham power station.

Overton, across the Lune, is an ancient village,

appearing as Oureton in the Domesday Book. Modern

building for commuters surrounds the old core of the

village, leaving few signs of the traditional activities of

shipbuilding and fishing. Even so, the aroma of the fields

and the sea remains. Farms are still active in and around

the village, and twice a day the tide laps on its shores.

A walk around Bazil Point, from where there used to

be a ferry to Glasson, involves stepping through tidal

debris but provides open views across the marshes and

the Lune estuary.

The most notable feature of Overton is St Helen’s

Church, which is said to be the oldest church in

Lancashire. The church itself is more reticent, claiming

only, on a notice board inside, that the west wall is

“11th century or earlier” and that other parts, such as

the doorway arches, are “of about 1140”. Whatever its

age, it must have been one of the most isolated of early

churches. In outward appearance, the church is rather

colourless, with uninspired windows. Inside, however,

the small church is transformed, with the windows now

enlivened. The arrangement is novel, with a gallery to

the west, the pulpit by the south wall, and

the 1830 extension on the north side having

no view of the altar to the east.

South of Overton, the tidal Lades

Marsh used to be the outlet for the low-lying

expanse between Heysham and the Heaton-Colloway ridge. Once known as Little

Fylde, it was, like big Fylde, a waterlogged

wasteland. A remnant can be seen at

Heysham Moss, a reserve managed by the

Wildlife Trust. The reserve is home to many

breeding and wintering birds. The centre

of Heysham Moss is relatively pristine,

with characteristic bog plants (such as bog

myrtle and round-leaved sundew), mosses

and liverworts, plus indigenous electricity

pylons.

Today, the whole area outside

Heysham Moss is a mosaic of green fields

lined with ditches and gutters that, after

intensively staring at, I conclude no longer

flow anywhere, let alone to Lades Marsh.

Therefore, according to my self-imposed rule in the Introduction

(“if rain falling on an area makes its way to the Lune

estuary then the area is within my scope”), I should

ignore the old Little Fylde. But if enough rain fell, then I

suspect the flood would flow to Lades Marsh.

The Top 10 churches in Loyne

(for the non-religious)

1. St Helen’s, Overton

2. St John the Baptist, Tunstall

3. St Mary’s, Lancaster Priory

4. St Mary the Virgin, Kirkby Lonsdale

5. St Andrew’s, Sedbergh

6. St Wilfrid’s, Halton

7. St Margaret’s, Hornby

8. St Wilfrid’s, Melling

9. St Mary’s, Ingleton

10. St Andrew’s, Dent

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (The Lune to Lancaster)

The Next Chapter (Into Morecambe Bay)

© John Self

Right: The Lune at the Golden Ball

Right: The Lune at the Golden Ball

Left: Aldcliffe Marsh, looking towards the Lakeland hills

Left: Aldcliffe Marsh, looking towards the Lakeland hills

Right: Two lines of pylons from Heysham Power Station

marching over the old breakwaters on the Lune

Right: Two lines of pylons from Heysham Power Station

marching over the old breakwaters on the Lune

Left: The Jessie Ashton Memorial

Left: The Jessie Ashton Memorial

Left: Baines Cragg

Left: Baines Cragg

Right: Across Quernmore to Clougha

Right: Across Quernmore to Clougha

Left: Glasson Canal

Left: Glasson Canal

Left: Glasson marina

Left: Glasson marina

Left: St Helen’s Church, Overton

Left: St Helen’s Church, Overton