The Run-Up

The Run-Up

Right: Part of my running arena: Brookhouse, Caton, Halton and the Lune valley from Quarry Road. A

standard short run is from Brookhouse to the Waterworks Bridge visible to the right. Quarry Road

is the road up to the windmills, to which I usually run across fields rather than up the road (when I

am fit enough).

Right: Part of my running arena: Brookhouse, Caton, Halton and the Lune valley from Quarry Road. A

standard short run is from Brookhouse to the Waterworks Bridge visible to the right. Quarry Road

is the road up to the windmills, to which I usually run across fields rather than up the road (when I

am fit enough).

Left: Dow Crag and Coniston Old Man to the Langdale Pikes, across the Lune valley, from near the windmills.

Left: Dow Crag and Coniston Old Man to the Langdale Pikes, across the Lune valley, from near the windmills.

Unfortunately, the weather has played its part in limiting my running. It rained all day Saturday and Sunday. The left photograph

shows my riverside path to the Waterworks Bridge (the little island is normally on my path, with the river beyond it). The

right photograph shows my path to the fishermen’s hut (this is normally a green field, with the river beyond the nearly

submerged fence). I later discovered that the footbridge I (used to) cross to reach the hut has been washed away. I doubt

that the Angling Club will be in hurry to replace it, as we are outside the fishing season. This is a pity, as the run up-river,

now out of commission, is serenely peaceful in winter, when the frisky bullocks of summer are no longer there. I liked to run

a little further up the river - to the hut, then to Claughton Beck, then to the River Wenning - as I became fitter.

Unfortunately, the weather has played its part in limiting my running. It rained all day Saturday and Sunday. The left photograph

shows my riverside path to the Waterworks Bridge (the little island is normally on my path, with the river beyond it). The

right photograph shows my path to the fishermen’s hut (this is normally a green field, with the river beyond the nearly

submerged fence). I later discovered that the footbridge I (used to) cross to reach the hut has been washed away. I doubt

that the Angling Club will be in hurry to replace it, as we are outside the fishing season. This is a pity, as the run up-river,

now out of commission, is serenely peaceful in winter, when the frisky bullocks of summer are no longer there. I liked to run

a little further up the river - to the hut, then to Claughton Beck, then to the River Wenning - as I became fitter.

Right: The fishermen’s hut by the Lune, with Whernside and Ingleborough some 15 miles beyond.

Right: The fishermen’s hut by the Lune, with Whernside and Ingleborough some 15 miles beyond.

Left: The track down from the Caton Moor trig

point past the windmills. (It is supposed

to be a bridleway but I have never seen

a horse here. I have never seen a runner

either, but there is the occasional walker

to spoil my solitude.)

Left: The track down from the Caton Moor trig

point past the windmills. (It is supposed

to be a bridleway but I have never seen

a horse here. I have never seen a runner

either, but there is the occasional walker

to spoil my solitude.)

Right: Some young fellow winning some race in about 1960.

Right: Some young fellow winning some race in about 1960.

Left: The bridleway up to the little bridge and the windmills.

Left: The bridleway up to the little bridge and the windmills.

Left: The River Lune and fishermen’s

hut (a different hut to that

shown in week 4), below

Lawson’s Wood. Ingleborough

is in the distance. This hut is

400 yards upstream of the

Waterworks Bridge. I ran here

after the heavy rain of a few

weeks ago, when the river was

full to the brim and lapping over

the green fields, which was

a scary experience. It is near

here that Ruth has seen one

of the otters that have recently

returned to the Lune. I haven’t

seen one yet: they can hear my

wheezing a mile off.

Left: The River Lune and fishermen’s

hut (a different hut to that

shown in week 4), below

Lawson’s Wood. Ingleborough

is in the distance. This hut is

400 yards upstream of the

Waterworks Bridge. I ran here

after the heavy rain of a few

weeks ago, when the river was

full to the brim and lapping over

the green fields, which was

a scary experience. It is near

here that Ruth has seen one

of the otters that have recently

returned to the Lune. I haven’t

seen one yet: they can hear my

wheezing a mile off.

Right: The Lune floodplain, flooded, as is its wont.

Right: The Lune floodplain, flooded, as is its wont.

Right: The River Lune from the old railway line

at the Crook o’ Lune.

Right: The River Lune from the old railway line

at the Crook o’ Lune.

The River Lune near where the River Wenning joins (I usually run along the left bank)

[1]. Shakespeare, William, Henry VIII, Act 1, Scene 4. Right: My run up [1] to the windmills this week was halted at

this gate when I saw four hares running around in the field

beyond. In Britain the hare has declined more than any

other mammal except the water vole but they seem content

enough on Caton Moor. I stopped and watched them for

several minutes. Of all the animals that I see on my runs,

I feel the most affinity with the hare (if I may so presume).

The others run, but usually in alarm; hares seem to run just

because they want to.

Right: My run up [1] to the windmills this week was halted at

this gate when I saw four hares running around in the field

beyond. In Britain the hare has declined more than any

other mammal except the water vole but they seem content

enough on Caton Moor. I stopped and watched them for

several minutes. Of all the animals that I see on my runs,

I feel the most affinity with the hare (if I may so presume).

The others run, but usually in alarm; hares seem to run just

because they want to.

Left: The end of the 1980 Preston-to-Morecambe Marathon. The

lady with the bag was disqualified for not running the

whole course.

Left: The end of the 1980 Preston-to-Morecambe Marathon. The

lady with the bag was disqualified for not running the

whole course.

Left: Skiddaw on April 2nd last year.

The fell-race route is up to the left of the gully at the right, past the tops of Jenkin Hill and Little Man,

and on to the top of Skiddaw, and back the same way.

Left: Skiddaw on April 2nd last year.

The fell-race route is up to the left of the gully at the right, past the tops of Jenkin Hill and Little Man,

and on to the top of Skiddaw, and back the same way.

Right: Littledale and Ward’s Stone (above the barn) from the Cragg.

Right: Littledale and Ward’s Stone (above the barn) from the Cragg.

40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79

6% 9% 13% 19% 27% 30% 38% 59%

The women’s figures are similar but distorted because

the modern breed of women marathon runner has not

yet worked its way through the age groups and because

very few women ran marathons forty years ago.

Left: The River Lune at the Crook o’Lune. I have three routes to the Crook,

two by the river and one along the old

railway line, giving six possible loops.

I could have a different run there, 4 or

5 miles, every day of the week (with a

rest day). I think I would be content if

that was all that I could manage, for

it is a fine stretch of river. In general,

though, I prefer to mix in some runs up

the hills (for the views), not that I have

managed much of that this week. After

the positive tone of the previous two

weeks, this has been a steady week

of consolidation: no real problems but

not much progress either.

Left: The River Lune at the Crook o’Lune. I have three routes to the Crook,

two by the river and one along the old

railway line, giving six possible loops.

I could have a different run there, 4 or

5 miles, every day of the week (with a

rest day). I think I would be content if

that was all that I could manage, for

it is a fine stretch of river. In general,

though, I prefer to mix in some runs up

the hills (for the views), not that I have

managed much of that this week. After

the positive tone of the previous two

weeks, this has been a steady week

of consolidation: no real problems but

not much progress either.

Right: On Tuesday I saw my first sand-martins of the year. Their return to the Lune valley in April is always welcome because

their whirling, twittering flight over the river is characteristic of the summer months. They come to nest in the tunnels they

build into the steep river banks. Unfortunately, the Tuesday sand-martins had mistimed their return. The Lune was in

flood. All their nests were underwater. The sand-martins, lots of them, were swooping over the turbulent river, puzzled.

The river had subsided by Wednesday but no doubt their nests were somewhat soggy. The photograph shows the path to

the Waterworks Bridge. The river is normally several metres lower in its bed to the right.

Right: On Tuesday I saw my first sand-martins of the year. Their return to the Lune valley in April is always welcome because

their whirling, twittering flight over the river is characteristic of the summer months. They come to nest in the tunnels they

build into the steep river banks. Unfortunately, the Tuesday sand-martins had mistimed their return. The Lune was in

flood. All their nests were underwater. The sand-martins, lots of them, were swooping over the turbulent river, puzzled.

The river had subsided by Wednesday but no doubt their nests were somewhat soggy. The photograph shows the path to

the Waterworks Bridge. The river is normally several metres lower in its bed to the right.

Left: Approaching the top of the Cragg from the other side.

Left: Approaching the top of the Cragg from the other side.

Right: Roeburndale, looking north, with Whernside to the right.

Right: Roeburndale, looking north, with Whernside to the right.

Left: Dow Crag and Coniston Old Man. On September 9th 1988 I ran from

the bottom right corner, to the basin (wherein lies Goats Water) between the two.

Then up the Old Man, north to Brim Fell, and back behind Dow Crag, returning

on the Walna Scar track. On May 15th 2005 I ran roughly the other way round,

up Dow Crag to Brim Fell and back over the Old Man.

Left: Dow Crag and Coniston Old Man. On September 9th 1988 I ran from

the bottom right corner, to the basin (wherein lies Goats Water) between the two.

Then up the Old Man, north to Brim Fell, and back behind Dow Crag, returning

on the Walna Scar track. On May 15th 2005 I ran roughly the other way round,

up Dow Crag to Brim Fell and back over the Old Man.

Left: Waterworks Bridge below Aughton Woods.

Left: Waterworks Bridge below Aughton Woods.

Right: The end of the 1982 Norfolk Marathon, in the

courtyard of Norwich Cathedral.

Right: The end of the 1982 Norfolk Marathon, in the

courtyard of Norwich Cathedral.

Right: The trig point on Wolfhole Crag (at 527

metres) in the Forest of Bowland, with

millstone grit boulders and heather.

(This photograph was taken on an

earlier occasion: I wouldn’t want you

to think that I ignored the ‘moor closed’

signs.) This moor is home to England’s

largest inland colony of lesser black-backed gulls. I was looking forward

to running amidst the cacophony of

25,000 nesting gulls. I would not have

felt guilty at disturbing them, as I’m

sure the land-owners would prefer

grouse to nest instead and, in addition,

all these gulls pollute Lancaster’s

water supply.

Right: The trig point on Wolfhole Crag (at 527

metres) in the Forest of Bowland, with

millstone grit boulders and heather.

(This photograph was taken on an

earlier occasion: I wouldn’t want you

to think that I ignored the ‘moor closed’

signs.) This moor is home to England’s

largest inland colony of lesser black-backed gulls. I was looking forward

to running amidst the cacophony of

25,000 nesting gulls. I would not have

felt guilty at disturbing them, as I’m

sure the land-owners would prefer

grouse to nest instead and, in addition,

all these gulls pollute Lancaster’s

water supply.

As it happens, I have not managed a

90-minute run this week, unlike a couple of

previous weeks. It is good to know that I am

capable of it but ... I hesitate to regale you

with a litany of my woes but I cannot give

the full and fair picture of my running that

you deserve without mentioning that I have

been somewhat discommoded this week by

bruises gained by falling in the beck. After

a dry spell, as we’ve had, I work on the bank

of the beck at the bottom of our garden

to protect it against erosion during a very wet spell,

as we will surely have. Anyhow, somehow, I fell in.

Afterwards, if I tried to run I would wince at every step.

I kept telling myself that “pain is inevitable; suffering is

optional” but I kept answering back “pain is optional;

running is not compulsory - walk instead”.

As it happens, I have not managed a

90-minute run this week, unlike a couple of

previous weeks. It is good to know that I am

capable of it but ... I hesitate to regale you

with a litany of my woes but I cannot give

the full and fair picture of my running that

you deserve without mentioning that I have

been somewhat discommoded this week by

bruises gained by falling in the beck. After

a dry spell, as we’ve had, I work on the bank

of the beck at the bottom of our garden

to protect it against erosion during a very wet spell,

as we will surely have. Anyhow, somehow, I fell in.

Afterwards, if I tried to run I would wince at every step.

I kept telling myself that “pain is inevitable; suffering is

optional” but I kept answering back “pain is optional;

running is not compulsory - walk instead”.

Left: Winder, Arant Haw and Calders, the ridge along which I ran.

Left: Winder, Arant Haw and Calders, the ridge along which I ran.

Right: Bowderdale in the Howgills, showing the eastern ridge that I ran

along. Randygill Top is the rounded peak (all peaks are rounded

in the Howgills!) to the right, with part of Yarlside to its right. The

slope of Yarlside is one of the ones that I could not run up.

Right: Bowderdale in the Howgills, showing the eastern ridge that I ran

along. Randygill Top is the rounded peak (all peaks are rounded

in the Howgills!) to the right, with part of Yarlside to its right. The

slope of Yarlside is one of the ones that I could not run up.

Left: Littledale, from the footpath between

Cragg Farm and Belhill Farm, is the kind

of place where I prefer to run. The grassy

ridge on the left, up to High Stephen’s

Head, is a fine run; the rocky ridge on

the right, up to Ward’s Stone, less so. I

can be certain that there will be no other

runners and no spectators. (I dare but

whisper that I eventually decided to run,

not rest, this week. The best that I can

say is that I haven’t made matters worse

but it feels as though my body is still re-assembling itself into working order.)

Left: Littledale, from the footpath between

Cragg Farm and Belhill Farm, is the kind

of place where I prefer to run. The grassy

ridge on the left, up to High Stephen’s

Head, is a fine run; the rocky ridge on

the right, up to Ward’s Stone, less so. I

can be certain that there will be no other

runners and no spectators. (I dare but

whisper that I eventually decided to run,

not rest, this week. The best that I can

say is that I haven’t made matters worse

but it feels as though my body is still re-assembling itself into working order.)

Right: Proof that I completed the 1984 London Marathon. I expect

the technology has improved by now but in those days a

photographer snapped runners at the finish line and sent

them a tiny photograph (which is what the above was - sorry

for the quality), defaced in some way, in this case, with the

‘proof’ printed over it. You could then pay a large fee for a

large photo as a memento of the occasion. I didn’t.

Right: Proof that I completed the 1984 London Marathon. I expect

the technology has improved by now but in those days a

photographer snapped runners at the finish line and sent

them a tiny photograph (which is what the above was - sorry

for the quality), defaced in some way, in this case, with the

‘proof’ printed over it. You could then pay a large fee for a

large photo as a memento of the occasion. I didn’t.

Left: Waterworks Bridge, across which I have run many times,

after it was opened to the public in the 1990s. Clougha

Pike is in the distance.

Left: Waterworks Bridge, across which I have run many times,

after it was opened to the public in the 1990s. Clougha

Pike is in the distance.

Left: Pinning my number on before the Windermere Marathon.

Left: Pinning my number on before the Windermere Marathon.

Right: The end of the Windermere Marathon.

Right: The end of the Windermere Marathon.

Left: The River Lune at the Crook o’Lune.

Left: The River Lune at the Crook o’Lune.

Left: An ex-tree near Aughton, symbolising my physical and

mental state at the beginning of the week.

Left: An ex-tree near Aughton, symbolising my physical and

mental state at the beginning of the week.

Left: A tree by the River Lune below Aughton Woods.

Left: A tree by the River Lune below Aughton Woods.

Left: The River Lune from Halton Bridge,

looking west to the M6 bridge in the

distance. I have not run across Halton

Bridge so often recently because a

bridge on the way to it has been closed

for ‘safety reasons’. This necessitates

a detour on the road. It is only a short

one but it changes the character of the

run. If it takes as long to repair the

bridge as it did the adjacent similar

one a few years ago then it is liable to

be out of action for many months. This

run also takes me past the site of the

proposed eco-houses but I can see no

sign of any work on them yet.

Left: The River Lune from Halton Bridge,

looking west to the M6 bridge in the

distance. I have not run across Halton

Bridge so often recently because a

bridge on the way to it has been closed

for ‘safety reasons’. This necessitates

a detour on the road. It is only a short

one but it changes the character of the

run. If it takes as long to repair the

bridge as it did the adjacent similar

one a few years ago then it is liable to

be out of action for many months. This

run also takes me past the site of the

proposed eco-houses but I can see no

sign of any work on them yet.

Right: From Slieve Donard to the Brandy Pad and Hare’s Gap.

Right: From Slieve Donard to the Brandy Pad and Hare’s Gap.

Left: Slieve League from the Cliffs of Bunglass.

Left: Slieve League from the Cliffs of Bunglass.

Right: Ballyness Bay from the Donegal cottage.

Right: Ballyness Bay from the Donegal cottage.

Left: Marble Arch, on the way to Horn Head.

Left: Marble Arch, on the way to Horn Head.

Left: The end of the Dooey Peninsula, Horn Head dimly ahead.

Left: The end of the Dooey Peninsula, Horn Head dimly ahead.

Right: Ghleann Bheatha with Loch Beagh.

Right: Ghleann Bheatha with Loch Beagh.

Left: The beach at Droim na Creige.

Left: The beach at Droim na Creige.

Right: The Giant’s Causeway.

Right: The Giant’s Causeway.

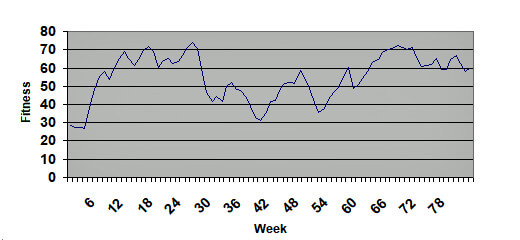

Right: My fitness according to the Fitnessometer.

Right: My fitness according to the Fitnessometer.

Left: Looking over Abbeystead from Hawthornthwaite Fell.

Left: Looking over Abbeystead from Hawthornthwaite Fell.

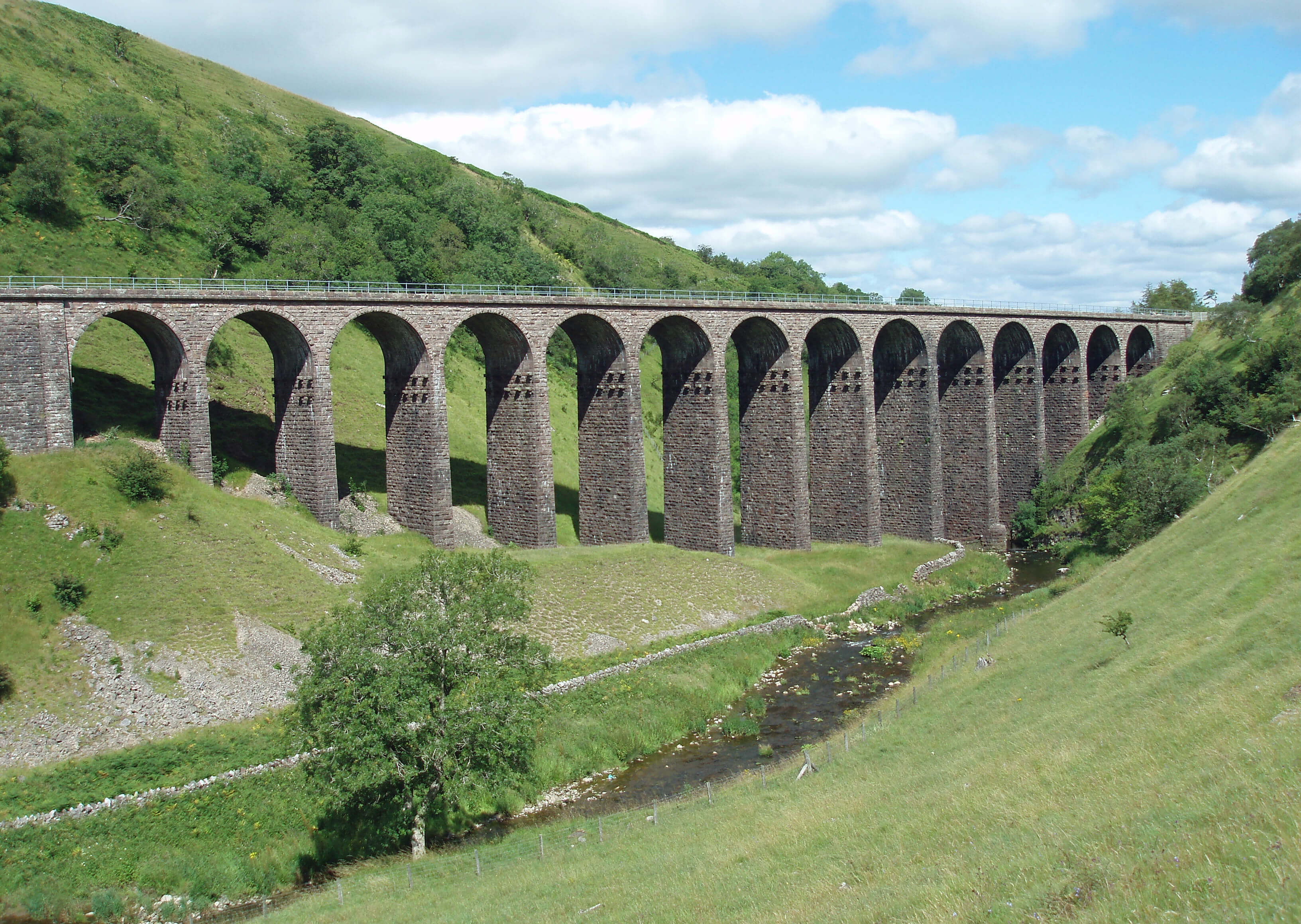

Left: Smardalegill Viaduct.

Left: Smardalegill Viaduct.

Right: Scotch Argus.

Right: Scotch Argus.

Right: Looking towards Ingleborough, up the Lune valley, from Halton Park on the other side of the river.

I ran through Halton Park on Wednesday after being tipped-out at Netherby, near Gressingham. I began by running in the

opposite direction, towards the Redwell Inn, and returned through Swarthdale and Addington. This was the second of two

one-hour-plus runs this week. I dare hardly believe how comfortably (touch wood) I’m progressing towards our target.

Right: Looking towards Ingleborough, up the Lune valley, from Halton Park on the other side of the river.

I ran through Halton Park on Wednesday after being tipped-out at Netherby, near Gressingham. I began by running in the

opposite direction, towards the Redwell Inn, and returned through Swarthdale and Addington. This was the second of two

one-hour-plus runs this week. I dare hardly believe how comfortably (touch wood) I’m progressing towards our target.

© John Self, Drakkar Press