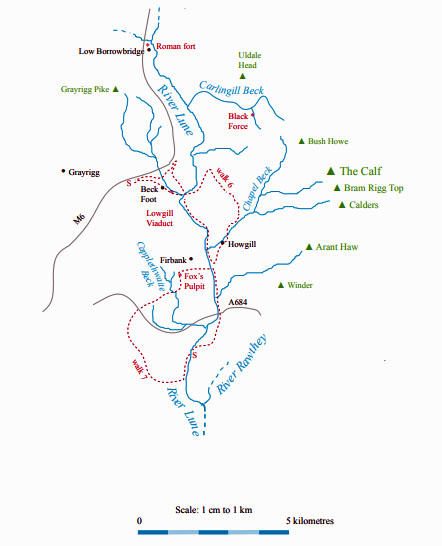

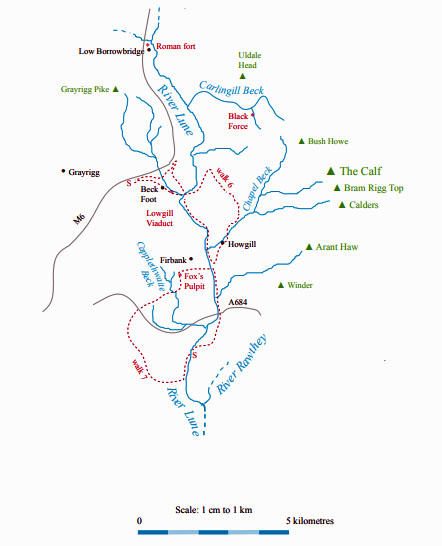

The Land of the Lune

Chapter 3: Western Howgills and Firbank Fell

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Shap Fells and Birkbeck Fells)

The Next Chapter (Upper Rawtheydale)

Chapel Beck, looking towards Bush Howe

The Lune from Borrow Beck ...

Right: Low Borrowbridge

Right: Low Borrowbridge

Just beyond the Borrow Beck junction at Low

Borrowbridge there is a flat, green field that seen

from the fells on either side looks like a sports arena,

which in a way it was because until the late 19th century

a large sheep fair used to be held here, with associated

sports and other activities. But long before that, from the

1st to the 4th century, this was the site of a Roman fort.

Somehow this fact became forgotten, despite the

reminder of Borrow (or burgh) Beck, until it was re-discovered in the early 19th century. This is especially

surprising since the site has been relatively undisturbed

by later building. The fort measures 130m by 100m,

adequate for five hundred soldiers. It lies on the Carlisle-Chester route and is the first of three sites of Roman

forts that we will meet. Excavations in the 20th century

have confirmed the layout of the fort but seem to have

uncovered few remains. More has been found at the

cemetery to the south, including a tombstone with the

touching inscription (not in English, of course): “Gods

of the underworld, Aelia Sentica lived for 35 years.

Aurelius Verulus erected this stone for his loving wife”.

Although the outline of the fort is clear, there is not much

to see on the ground, only ramparts along the line of the

old walls and on the west side a few ditches. Some claim

that, ignoring the railway, motorway and A685 (quite a

feat), the line of an aqueduct can be made out running

towards the fort from the slopes below Grayrigg Pike.

Grayrigg Pike is seen by many but noticed by few.

The steep crags and slopes around Great Coum and

Little Coum make them the most scenic cliffs we have

met so far but the rebounding noise of M6 traffic lessens

their appeal to walkers.

The Lune passes under Salterwath Bridge. We have

met a few ‘wath’s already and, as you might suspect, it

is an old word (Viking, in fact) for a ford. The bridge

itself was last rebuilt in 1824. At about this point, the

drove road that followed the Lune from Greenholme

swung west to skirt Grayrigg and climbed to the Lune

watershed, which it more or less followed south to

Kirkby Lonsdale.

Beyond Low Carlingill farm, the Lune meets the

most dramatic beck of the Howgills, Carlingill Beck.

Carlingill Beck

Carlingill Beck and the River Lune mark the

northwestern boundary of the Yorkshire Dales

National Park. Today this seems anomalous. A boundary

has to be somewhere but there seems no discernible

reason for it to include the southern part of the Howgills

but to exclude the northern part, as they are the same

in terms of geology and scenery. The boundary is here

simply because the old Westmorland-Yorkshire county

border lay along Carlingill Beck at the time the National

Park was established in 1954.

[Update: As has been remarked in previous updates,

the National Park boundaries were changed in 2016.

All of the Howgills are now within the Yorkshire Dales.]

The Yorkshire Dales National Park occupies some

1760 sq km and is the third largest of Britain’s fourteen

National Parks. The part we encounter in the Howgills is

uncharacteristic of the Dales, which are normally pictured

in terms of spectacular limestone scenery. The Yorkshire

Dales are no longer all in Yorkshire: the Howgills,

Dentdale and Garsdale are in Cumbria. (Some diehards,

usually Yorkshiremen, consider that the 1974 boundaries

defined new administrative regions and had nothing to do

with the traditional counties. The fact that the new regions

were also called counties and that many of them used old

county names was unfortunate but irrelevant. On that basis,

the southern Howgills, Dentdale and Garsdale continue to

be in (the traditional county of) Yorkshire and are also in

(the new administrative region of) Cumbria.)

As we will see, only a few of the Dales lie within Loyne

– Dentdale, Garsdale, Kingsdale and Chapel-le-Dale. The

Lune is the western border for 12km and Lunesdale is not

sensibly regarded as one of the Yorkshire Dales.

Like all British National Parks, the Yorkshire Dales

National Park is not state-owned but consists of privately

owned estates and farms administered by an authority

responsible for conservation and recreation. It is therefore

both a tourist attraction and a working area, which even

includes some large quarries.

Left: Upper Carlingill Beck, with The Spout

middle right

Left: Upper Carlingill Beck, with The Spout

middle right

Right: The exposed rocks on the western slopes of

Black Force, with Carlin Gill and Grayrigg beyond

Carlingill Beck is an excellent site for students of

fluvial geomorphology (that is, of how flowing water

affects the land), providing some good illustrations of

post-glacial erosion. The beck arises as Great Ulgill

Beck below Wind Scarth and Breaks Head, on a

ridge that runs from The Calf, and then curves west at

Blakethwaite Bottom, a sheltered upland meadow below

Uldale Head. It enters an increasingly narrow gorge,

with contorted rock formations exposed on the southern

side, giving us our first real view of the Silurian slate

of the Howgills. The beck then forms The Spout, which

is as much a water shoot as a waterfall, as it tumbles

steeply over 10m of tilted rocks. To the north are

steep screes and further exposed contorted rocks

and below to the south looms the deep, dark gash

formed by Little Ulgill Beck.

Here is Black Force, the most spectacular

scene of the Howgills: not one force but a series

of cascades, deep within a V-shaped ravine that

has remarkable rock formations exposed on its

western side. Our journey through the northern

Howgills showed us little to hint at the striking

degree of erosion hidden within this gill.

Black Force (the scale may be judged

by the two walkers and a dog on the path

top right - you can’t see them? - precisely)

Beyond admiring the awesome sights, we

might wonder about causes and effects. The

benign, smooth slopes of the Howgills do not

suggest the convulsions needed to form the

contorted rocks seen by Carlingill Beck. Are

these contortions limited to Carlingill Beck, or

are there similar rock formations hidden elsewhere? If

the latter, why have they been so dramatically exposed

only here, in such deep gullies, from such relatively

small becks? Or did the contortions cause weaknesses

that the becks have exploited?

Below Black Force, Carlingill Beck begins to

calm down. It still runs in a narrow valley, with small

waterfalls and eroded sides, but, as becks tend to do,

it eventually levels off and opens out. The lower parts

of Carlingill Beck and its tributaries, especially Grains

Gill, still show fine examples of post-glacial erosion,

in the form of deep gullies, alluvial fans and cones.

The relative absence of human and animal disturbance

and the frequency of heavy flooding enable the study

of hillside erosion, the changes of flow directions, and

the dynamics of debris flow and deposition. Even to the

non-expert, the scenes provide remarkable evidence of

the continuing impact of erosive forces.

The beck passes under the old Carlingill Bridge.

Being on a county border is a problem for any self-respecting bridge: in 1780, when Carlingill Bridge

was dilapidated, Westmorland quarter sessions ordered

a contract to rebuild half of it. Happily, the bridge

is now all in Cumbria. Unhappily, it was still in need

of repair when I last visited. There is a final burst of

energy as Carlingill Beck runs through the narrow gorge

of Lummers Gill to enter the Lune but, under normal

conditions, it still seems far too demure to have caused

the effects seen upstream.

Any walkers who have strolled in Bowderdale and

Langdale and are wondering about an outing along

Carlingill Beck should be warned that this is a more

serious undertaking. Walking by the beck itself involves

a fair amount of rough scrambling and, if the beck is

high, may be impossible. Black Force cannot be walked

up, although it is possible to clamber up the grassy slope

to the east. The path to The Spout is increasingly difficult

and it likewise becomes impassable, although there is

a challenging escape to the north. The public footpath

from the south past Linghaw, which can be continued to

Blakethwaite Bottom, provides no view into the Black

Force ravine.

The Lune from Carlingill Beck ...

Left: Sheep below Fell Head

Left: Sheep below Fell Head

Right: Fell pony and the River Lune from Linghaw

According to a generally accepted theory, long

ago the Lune used to begin about here. It is

believed that the Lune was then formed from the

becks that drain south from the Howgills, with

all the becks we’ve met up to now (Bowderdale

Beck, Langdale Beck, Borrow Beck, and so

on) at that time flowing north within the Eden

catchment area. The Lune watershed was then

south of what is now the Lune Gorge. In time,

the headwaters of the Lune eroded northwards to

capture Borrow Beck and then all the other becks

to divert their flow southward. The evidence for

this is complicated, involving the ‘open cols’ to

the north through which no water now flows,

or much less water than the size of the valleys

would suggest; the fact that the flow of the

northern becks is discordant to the underlying

rocks; and the history of geological uplifts and

tilts. The more recent glaciation has obscured

most of this evidence for the untutored eye.

Above the Lune is Gibbet Hill, where the

bodies of miscreants were displayed and where

alleged eerie noises are now drowned by the M6.

The small road to the east of the Lune, Fairmile

Road, is along the line of the Roman road that

led south from Low Borrowbridge. A part of the

Roman road that diverges from the present road

was investigated in 1962. At Fairmile Gate, the

road crosses Fairmile Beck, which runs from the

hills by Fell Head and Linghaw, which are good

vantage points for the Lune valley. Fell Head is

one of the more identifiable hills of the Howgills,

having a covering of heather and hence a dark

appearance.

The Lune reaches the Crook of Lune Bridge,

which is the quirkiest of all the Lune bridges. It

is a sturdy yet graceful 16th century construction,

with two 10m arches and a width of about 2m.

Being a little upstream of the two lanes that

drop down to it, it makes a tricky manoeuvre for

vehicles. It’s as though the 16th century builders

wanted to ensure that no 21st century juggernaut

could cross.

At the bridge we meet the Dales Way at

exactly the point that it leaves (or enters) the

Dales. The Dales Way is a 125km footpath

between Ilkley and Bowness-on-Windermere, passing

through many of the most attractive dales, especially, if

I may say so, this stretch of the Lune.

Crook of Lune Bridge

Just beyond the bridge, Lummer Gill joins the

Lune, having run from Grayrigg Common, through

Deep Gill, under the motorway and railway (where,

thankfully, they veer away from the Lune valley), past

the village of Beck Foot and then under the magnificent

curved Lowgill Viaduct. The eleven red arches stand

30m high and seem so thin as to be flimsy but for over

a hundred years (1861 to 1964) they carried trains on

the Lowgill-Clapham line, a central part of the Loyne

railway network. A failure of railway politics meant

that it was never used as originally intended, that is, for

Ingleton to Scotland traffic – until the winter of 1963

blocked the Settle-Carlisle line. Thanks to the work of

the British Railways Board (Residuary) Ltd in 2009 the

viaduct is no longer the aerial arboretum it had become,

with shrubs and trees sprouting from the track.

Lowgill Viaduct

The Lune accompanies the Dales Way for 2.5km.

This is a gentle, bubbling stream in summer, but a

torrent after heavy rain on the Howgills. Debris in the

tree branches shows that the floodplains are indeed

occasionally under water.

This is a good stretch along which to spot the

dipper, the bird that best represents the spirit of the

becks. It is the only passerine (that is, perching bird) that

is adapted to aquatic life, in being able to close its ears

and nostrils under water, having no air sacs in its bones,

and in being able to store more oxygen in its blood

than other passerines. It uses its wings to swim under

turbulent water in its search for insect larvae. It will be

seen bobbing on a rock or flying fast and direct, low over

the water.

The presence of dippers along any beck is a measure

of the health of that beck. Sadly, the number of dippers

seems to be declining along the Lune and its tributaries,

probably because of the damage to riverbanks, where it

nests, and the building of weirs for flood control, which

reduces the turbulence that dippers need.

The Top 10 birds in Loyne

1. Dipper: for its spirit

2. Curlew: for its call

3. Lapwing: for its flight

4. Kingfisher: for its colour

5. Skylark: for its song

6. Oystercatcher: for its bill

7. Heron: for its style

8. Hen harrier: for its rarity

9. Sand martin: for its nest

10. Swan: for its grace

Honourable mention: the snipe.

Ellergill Beck, running from Brown Moor past

Beck House, and the more substantial Chapel Beck

next supplement the Lune. Chapel Beck is the largest

beck of the western Howgills. The western slopes below

Arant Haw, Calders, Bram Rigg Top, The Calf, White

Fell Head and Breaks Head all contribute to it. Its slopes

also have two of the clearest paths in the Howgills, on

either side of Calf Beck, providing an excellent walk

to The Calf. On this walk you would see the Horse of

Bush Howe. This is a natural (it seems to me) rocky

outcrop in the vague shape of a horse, although there are

stories that in the past people devoted a day each year to

keeping the horse in shape. (The horse can be seen in the

photograph at the beginning of this chapter: it is bisected by the shadow on

the hill middle right.) One legend is that it was created

as a signal for smugglers in Morecambe Bay. One can

only smile at the misguided attempts to add a touch of

glamour to the Howgills, and move on.

Looking towards Arant Haw and Brant Fell

Right: Holy Trinity Chapel, Howgill

Right: Holy Trinity Chapel, Howgill

After Castley Wood, Chapel Beck passes through

what is, if anywhere is, the centre of the scattered

parish of Howgill, which gives its name to the whole

area. The Holy Trinity Chapel, built in 1838, presents

an unreasonably pretty picture, with its narrow windows

and its neatly shaped bushes and with the old mill,

school and cottages nearby. Below the chapel we see an

example of the work of the Lune Rivers Trust.

The Lune Rivers Trust (formerly the Lune Habitat Group)

was formed in 1997 to help protect watercourses, regenerate

habitats, and encourage the biodiversity of the Lune - and

its tributaries, for of course the Lune cannot be healthy if

its tributaries are not. The aim is to improve landscapes,

reduce erosion and safeguard water quality. The Trust is a

public charity aiming to develop coordinated programmes

of action involving farmers, land-owners, national parks,

government ministries, angling clubs, and anyone else with

a concerned interest in the Lune.

Some of the Lune’s problems are attributed to the

damage that sheep and cattle cause to riverbanks. Therefore,

as at Chapel Beck, the Trust has carried out a programme

of fencing and tree planting in order to stabilise the banks.

So far, some 60km of riverbank have been protected, to

benefit wildlife such as otters, water voles, kingfishers and

dippers, as well as fish populations.

The maturing Lune runs deep below grassy slopes,

passing under the Waterside Viaduct, which is notable

for being the highest bridge across the Lune, 30m above

the heads of walkers on the Dales Way. Like the Lowgill

Viaduct, the Waterside Viaduct used to carry the Lowgill-Clapham railway and is a fine structure, although here the

seven arches are of irregular size and the middle section

is of metal. Both viaducts are Grade II listed structures

and, like the Lowgill Viaduct, the Waterside Viaduct has

recently been renovated.

Waterside Viaduct

Walk 6: Lowgill and Brown Moor

Map: OL19 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: The roadside verge by the railway before the road drops down to Beck Foot (610964).

This walk includes the best stretch of path beside the Lune and a taste of the Howgills, without going to the highest tops. The

initial noise of the motorway and railway perhaps adds to our appreciation of the serenity of the Lune valley.

Walk east to the B6257 (with the Lowgill Viaduct directly ahead) and pass under the viaduct, noticing the packhorse bridge

dwarfed under it, to Crook of Lune Bridge. Immediately after the bridge, turn left, taking the path above Nether Fields Wood to

Brunt Sike. Then double back, walking across fields to Gate House.

Continue to Beck House and Beck Houses Gate, beyond which you are on the open fell. Walk up Brown Moor (412m) and

stop to admire the view, from Fell Head on the left to Brant Fell on the right. There’s a good view of the so-called Horse of Bush

Howe but better is the sight of the neatly interlacing ridges up the various valleys.

Walk south to Castley Knotts, drop down to the footpath, and follow it through Castley to Gate Side. Walk south on the road

and turn right after Chapel Beck, past the Holy Trinity Chapel, and take the track to Thwaite, where the path is rather hidden

behind the barn to the left. Continue towards Hole House but don’t go that far: at Smithy Beck drop down to the Lune. Now

you follow the Dales Way back to the Crook of Lune Bridge. Route finding is no problem, so you may concentrate on spotting

dippers, kingfishers, herons, and other riverside birds.

From the bridge you could return the way you came or, trusting the OS map (for there is no signpost), turn right across fields

to Nether House, which although marked on the map is just a small pile of rubble. Walk up its old drive and detour right along the

road for 400m to view the neat, red Railway Terrace. Return past Lowgill Farm, turn left on the B6257 and right through Beck

Foot back to the starting point and the noise of modern transport.

Short walk variation: For a short walk I’d suggest heading straight for Brown Moor and back via Castley Knotts. So, walk over

the Crook of Lune Bridge, east for 1km, turn left through Riddings, on to Gate House, then up to Brown Moor and Castley

Knotts, and back west past Castley and Cookson’s Tenement and on 3km to the starting point.

Right: The stained glass windows of the Vale of

Lune chapel, which illustrate nature rather than

religious themes

Right: The stained glass windows of the Vale of

Lune chapel, which illustrate nature rather than

religious themes

The Lune accepts the tributary of Crosdale Beck,

which runs off the slopes of Arant Haw, and moves

towards the 17th century Lincoln’s Inn Bridge. Sadly,

Mr Lincoln and his inn are no longer with us, and some

might wish the same of the bridge, as it makes a narrow,

awkward turn on the busy A684. Like most bridges, it

forms a better impression from the riverside.

Here we detect some pride in being next to the Lune,

for as well as the farm of Luneside there is, just along the

A684, a Vale of Lune Chapel, now called St Gregory’s.

This was built in the 1860s, whilst the railway line

was being constructed, and, judging from its unusual,

robust design, it may have been built by rail workers.

This supposition is perhaps supported by a comment

in a booklet about the chapel that it was designed to be

“a plain building of studied ugliness”. Would a proper

architect take on such a challenge?

Opposite Luneside, Capplethwaite Beck enters the

Lune.

Capplethwaite Beck

Capplethwaite Beck and its tributary Priestfield Beck

run from Firbank Fell behind the ridge to the west

of the Waterside Viaduct. This unprepossessing moor

is known only for two things: Fox’s Pulpit and its

magnificent views of the Howgills.

From the plaque at Fox’s Pulpit there is a view

south along the Lune valley to the Ward’s Stone ridge

of Bowland Fells, 35km away. However, there is no

view of the Howgills, which is strange. One of the

Quaker beliefs, as noted in Fox’s journal, is that “the

steeplehouse and that ground on which it stood were

no more holy than that mountain”. Surely Fox would

have positioned himself about 200m east so that when

expressing such a sentiment he could gesture towards

the Howgills. That would convince anyone, and I could

even imagine listening to a three-hour sermon myself

if I could look at the Howgills at the same time. There

is still a graveyard by Fox’s Pulpit but the church that

Fox disdained has left in a huff, demolished by a gale

in 1839.

Fox’s Pulpit marks one of the few events in Loyne to be

considered of national importance. Here on June 13th 1652

George Fox preached to one thousand people for three

hours, according to his own journal, an event nowadays

often regarded as establishing the Society of Friends (or

Quakers).

The Quaker movement has been particularly

influential in the Loyne region. No doubt the emphasis on

equality and on the spirituality within people, rather than

churches, rituals and sacraments, appealed to independent,

poor northerners.

The mid 17th century – Oliver Cromwell, Civil

Wars, and so on – was a fertile, if challenging, time for

non-conformist religious movements but Quakerism was

a social movement as well, because the promotion of

equality naturally upset the privileged, powerful members

of society who did not receive from Quakers the respect

or deference they expected. This partly explains the years

of persecution suffered by Quakers. Fox himself was

imprisoned seven times.

It also explains the large number of ‘meetinghouses’

that we will pass. Quakers did not build churches, as it

was against their beliefs and would have been asking for

trouble. To begin with, they met within one another’s

houses. In some Loyne valleys almost every farmstead

may be described as an old Quaker meetinghouse – that

is, an old farmstead within which Quakers met. After the

Restoration of the monarchy (1660), matters gradually

improved for Quakers but the laws under which they had

been persecuted were not ended until the 1689 Act of

Toleration.

Incidentally, given the Quakers’ views on the

established church, is it coincidence that the two

becks’ names (Capplethwaite (chapel-meadow?) and

Priestfield) should assert their religiosity?

The name of Firbank is in fact known for a third

reason, at least by Australians: Firbank Grammar School

is one of the leading private schools in Australia. Another

coincidence? No, it was established in 1909 by Henry

Lowther Clarke, archbishop of Australia, who was born

at New Field, Firbank, 1 km south of Fox’s Pulpit.

The footpaths of Loyne pass through many hundreds

of farmsteads. I have found (with but one exception,

which I prefer not to dwell upon) that residents welcome,

or at least accept or are resigned to, strangers wandering

through their yards. I have also found an extraordinary

range of objects within these yards, showing that many

farmsteads are no longer farming or have needed to

diversify in order to supplement their farming income,

which is indicative of the continually evolving rural

character of Loyne. For example, at Shacklabank, 2km

south of Fox’s Pulpit, there is a gypsy caravan in the

yard (actually, I recall a set of them but the website says

that there is only one: I will have to return and count

them or it). This provides accommodation for visitors on

“free range walking holidays” or who consider mucking

in on the farm a holiday. This development received a

Cumbria Tourism Award in 2008.

Capplethwaite Beck runs past the 16th century

Capplethwaite Hall, which was the home of the Morland

family, one of whom, Jacob, was painted in 1763 by

George Romney before he became so obsessed with

Emma (later Lady) Hamilton that he painted her sixty

times. This portrait is now in the Tate Britain gallery,

and a grand figure he looks, although not as grand as the

Howgills behind, which unfortunately he is obscuring.

The western Howgills from Dillicar

Walk 7: Fox’s Pulpit and the Waterside Viaduct

Map: OL19 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: Killington New Bridge (623908).

Walk south by the Lune to Bowersike and take the track up to Greenholme, where there’s a good view back to Winder,

Baugh Fell and Middleton Fell. Through Greenholme, follow the wall on the right that swings north. Across a small beck, the

track turns west towards a plantation where there’s a reassuring footpath sign. It’s quiet here, among the bracken and heather, but

from the corner of the plantation you see, a few kilometres away, reminders of the 21st century – Killington Service Station and

the Lambrigg wind turbines.

Beyond the plantation the path drops down to a white gate, where you turn right to another white gate, from which there

is a view of the Howgills from Winder to Fell Head. Note the prominent white building 2km ahead (New Field), which is your

next objective.

Cross the A684. There is no clear path on the CRoW land but make your way across to Ghyll Farm, which is on Capplethwaite

Beck. There seem to be no signposts at Ghyll Farm, so be careful to turn left off the drive, before a barn, heading north. After

500m you reach the white building you noted before.

[Update: A reader says that a more accurate description of the

path from Ghyll Farm is "to turn left off the drive, to the left side of a large barn, ending up

behind it, from where the path heads north through a gate. There is another small gate in the wall across the

field which you need to go through". I'll take the reader's word for it - all I remember now is

that I became somewhat puzzled around Ghyll Farm.]

From New Field, walk 1km along the road to Fox’s Pulpit. By now, you might appreciate that Fox did well to attract a

thousand people up here. Walk east across the CRoW land of Knotts and, when the view ahead is revealed, pause to relate the

panorama to your map – in particular, identify the large farm of Hole House, 1km northeast. Head in the general direction of Hole

House until you reach either a wall or a clear footpath running north-south (between Stocks and Whinny Haw). In the former

case, follow the wall to the right until the footpath is reached.

Walk to Stocks and continue on the road north but before Goodies turn right over the old railway line and cross the Lune

footbridge. Walk up by Smithy Beck to Hole House. You are now on the well sign-posted Dales Way. Follow this for 3km past

the Waterside Viaduct, Lincoln’s Inn Bridge and Luneside.

Short walk variation: From the bridge, walk west, first on the road and then on a footpath, to Grassrigg. Walk south 200m to gain

the footpath that runs north above Grassrigg. Cross the A684 and take the path to Shacklabank. Walk north for 500m to take the

path that drops through Hawkrigg Wood, across the B6257, to Lincoln’s Inn Bridge. Follow the Dales Way south and where it

turns left to The Oaks, turn right to the Lune and back to Killington New Bridge.

The Lune from Capplethwaite Beck ...

Left: The Lune at Killington New Bridge

Left: The Lune at Killington New Bridge

Right: The Lune at Stangerthwaite

Paddlers (in a canoe, that is) feel the adrenaline

rising as they and the Lune approach the next

section, which includes a narrow rapid called the Strid

that drops 2m into a large pool. This is the liveliest

part of the whole Lune, as it tumbles through and over

sloping rocks and into deep pools, and one of the most

challenging canoeing stretches in northwest England.

(An experienced outdoor instructor died here in 2007.)

It may be viewed from a footpath that leads north from

Killington New Bridge. The bridge has a single 18m

arch and is not new. A proposal to build holiday chalets

in the field southwest of the bridge would, if accepted,

enable many more visitors to enjoy, or spoil, the scenic

tranquillity of the region.

At the bridge there used to be a notice: “SAA No

canoeing”. I expect that SAA is the Sedbergh Angling

Association but I was unsure of the legal status of their

notice. The SAA presumably owns the banks and can

insist upon private fishing. Does it own the Lune too? Can

it prevent others using the Lune? Obviously, they would

prefer canoeists not to tangle their lines and disturb their

fish. Indeed, I would prefer canoeists not to disturb the

dippers, kingfishers, and other wildlife (and anglers not

to disturb salmon, come to that). Nevertheless, canoeists

do tackle the Lune and its tributaries, with or without

permission, and good luck to them. The notice was

replaced in 2008 to read “Private fishing SAA”, which

seems more reasonable.

Canoeists will, I imagine, be also concerned with

the dangerous-looking weir that follows at Broad Raine.

Further south, at Stangerthwaite, the public bridleway

and ford seem impenetrable, at least to horses and

vehicles. It used to link two tracks, one of which leads

up to Four Lane Ends, the other three old lanes now

forming the A683 and B6256.

After this turbulent stretch, the Lune swings west to

meet the largest tributary so far, the River Rawthey.

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Shap Fells and Birkbeck Fells)

The Next Chapter (Upper Rawtheydale)

© John Self, Drakkar Press

Right: Low Borrowbridge

Right: Low Borrowbridge

Left: Upper Carlingill Beck, with The Spout

middle right

Left: Upper Carlingill Beck, with The Spout

middle right

Left: Sheep below Fell Head

Left: Sheep below Fell Head

Right: Holy Trinity Chapel, Howgill

Right: Holy Trinity Chapel, Howgill

Right: The stained glass windows of the Vale of

Lune chapel, which illustrate nature rather than

religious themes

Right: The stained glass windows of the Vale of

Lune chapel, which illustrate nature rather than

religious themes

Left: The Lune at Killington New Bridge

Left: The Lune at Killington New Bridge